Thalia Anthony

March 2021

COVID-19 and Long Bay Prison

Long Bay Correctional Complex had the first confirmed COVID-19 case in an Australian custodial setting. Located on a sprawling property at Malabar, Sydney, Long Bay is one of Australia’s largest prisons. On 25 March 2020, two employees at the Long Bay Forensic Hospital on the prison complex tested positive to COVID-19. Corrective Services NSW subsequently reported ‘the first case of COVID-19 in a NSW prison … a health care worker at Long Bay Hospital.’

The Long Bay correctional complex encompasses minimum and maximum security prisons, as well as a maximum-security prison hospital. In 2018–19, it detained 1518 people – over ten per cent of the total NSW prison population of 13,458 that is currently spread across 38 prisons (Tang and Corben 2020, 10).

Established in 1909, Long Bay has a notorious history. It has a record of deaths in custody, including Dunghutti man David Dungay Junior in 2015. Long Bay Hospital has accounted for one third of all NSW deaths in custody over the past two years, with the highest number of deaths in the state: 11 in 2018–19 and 4 in 2019–20.

Long Bay is an imposing facility, and its complex is surrounded by high fences, barbed wire and brick walls. Adjacent to the complex are affluent south-eastern suburbs, a golf course, and beaches.

The menacing external structure is mirrored internally. Contiguous cells cramp men in small spaces with little natural light or external stimulus.

COVID-19 intensified confinement at Long Bay prison, including increased time in cells. Tightly shared spaces, extended lockdowns, and prohibitions on visits epitomised the conditions in most Australian prisons in 2020. The growing prison population in recent decades, coupled with a pandemic, resulted in a crisis of incarceration. COVID-19 highlighted issues of substandard health services and human rights that come from managing large populations behind bars.

Imprisonment as Pandemic and its Acute Features Under COVID-19 Restrictions

Imprisonment is a social ‘pandemic’ that has reproduced rapidly, crossed borders, and impacted lives globally. In Australia, the increase in people in prisons – by almost 100 per cent from 21,714 in 2000 to 41,060 in 2020 – has dramatically outstripped the overall population growth increase of approximately 30 per cent. This imprisonment growth is matched by other Western countries, especially in North America. First Nations people carry a disproportionate burden of this increase due to settler-colonial legacies of carceralism and systemic racism.

Prison inflicts a ‘social death’ through its dehumanisation and exclusion, as Joshua Price (2015), building on the work of Orlando Patterson, has recently argued. People in prison experience ‘natal alienation’ from their communities and place, akin to slavery, and are rendered non-citizens (Patterson 1982). Incarceration also has biological dimensions that threaten the health and wellbeing of imprisoned people and their families. Deaths in custody and high rates of disease are the culmination of everyday physical and mental health issues arising from imprisonment.

Trapped in confined, over-crowded carceral spaces with inadequate sanitation, screening, and health services, disease proliferates. Infrastructural inequalities between carceral and non-carceral environments mean that those incarcerated are less likely to access life-saving healthcare, preventative medications, and support-people who can advocate for their health needs. However, threats to health have reached new heights during the COVID-19 pandemic. In early 2020, prisons in Wuhan city accounted for half of the city’s COVID-19 cases. In the United States, by mid-2020, people in prison were 5.5 times more likely to become infected than in the general population (Saloner et al 2020). The COVID-19 death rate is three times greater for incarcerated people than the general US population, with African Americans constituting 48 per cent of prison deaths.

Unlike the COVID-19 pandemic, governments have not sought to suppress or eliminate the prison pandemic. Rather, they have engineered its growth by building more prisons, deploying more police with greater powers, and amending sentencing and bail legislation in punitive directions. The coronavirus pandemic has driven home the threat to health inside the expanding prison complex. However, it has also spurred resistance as anti-prison activists have used COVID-19 as an opportunity to build their movement – hand in hand with Black Lives Matter protests and uprisings within prisons. This remainder of this article considers the recent protest at Long Bay Correctional Complex in Sydney and how coalition-building on the inside and outside of prisons has augmented the potential for abolition.

Australian Prisons and COVID-19

In Australia, people in prisons, their advocates, and prison authorities have been on high COVID-19 alert since March 2020. However, these groups have radically different strategies to protect the lives of those inside. On the one hand, authorities have imposed greater restrictions: cutting off prison visits, services, programs and work; extending in-cell lockdown and enforcing solitary confinement (Caruana 2020). Cleaning duties of common spaces were delegated to incarcerated people, increasing the risk of exposure to potential infection.

On the other hand, Australian advocates have called for the mass release of people from prisons. They raise concerns that prisons are over capacity, producing crowded indoor spaces in which COVID-19 thrives. Aboriginal Legal Services CEO Karly Warner stated that ‘[o]vercrowded prisons are not equipped to deal with a deadly pandemic.’ Advocates have also lobbied for COVID-19 testing, PPE, sanitation, health services, and the protection of human rights. Decarceration is consistent with the position of the World Health Organization and other international organisations, and the Communicable Diseases Network Australia.

First Nations organisations and families have campaigned to have First Nations people released as a priority due to chronic illness, over-incarceration, and systemic racism in healthcare. Makayla Reynolds, whose brother Nathan died in custody, fears that the prison system will not cope under the weight of a pandemic. She states:

I feel like if prisons couldn’t cope with my brother’s medical emergency back then, then how on Earth are they going to cope with a medical emergency from COVID-19? My brother, a proud Aboriginal man and loving dad, had a known asthma condition and couldn’t survive the conditions of a minimum-security prison. How on Earth will our people held in prisons survive a pandemic? They wouldn’t.

The policy predilection for restrictions over release prevailed from March until December 2020. While some rights, such as personal visits, resumed in late 2020, their reinstatement was often measured (i.e. no touching and half-hour limits). Other restrictions, such as mandatory quarantining for two weeks upon admission, remain. The restrictive approach in Australia counters the prison policy of many other governments. Globally, governments have decarcerated hundreds of thousands of people in recognition that release protects both people inside and the wider community (Londoño et al. 2020). Prison restrictions in Australia have not prevented the entry of COVID-19 as there have been outbreaks in Australian youth and adult prisons. In mid-2020, there were cases in six Victorian facilities, although there have been no COVID-19 deaths in Australian prisons (as of 18 February 2021).

According to a survey by Deadly Connections of 63 people (primarily in NSW prisons) and their families, 98 per cent had their mental health and wellbeing ‘negatively impacted’ and 50 per cent were ‘massively’ affected. Restrictions and the fear of COVID-19 have contributed to prison unrest internationally, as well in NSW, since the outbreak of the pandemic.

Resistance at Long Bay

The pandemic has intensified fears among people inside, especially First Nations people, that imprisonment will amount to a death sentence. On 8 June 2020, a Long Bay protest demonstrated solidarity with the growing movement against First Nations Deaths in Custody. Official accounts by Corrective Services NSW of the events drew attention to fights among inmates and drug-related activity occurring on the day. This account dismissed a key feature of the unrest – the BLM (Blak Lives Matter) protest. Six people in Long Bay spelled ‘BLM’ on the grass of the Long Bay Hospital. In a public statement, the protesting Prisoners of Long Bay Jail stated:

There was no permission for our representative Inmate Development Committee to speak to the media about our views on the George Floyd killing, the David Dungay killing and the changes recommended by the Coroner. We couldn’t report on how nothing has changed and the certainty that deaths in custody will continue through this brutal treatment.

In Sydney, tens of thousands of people protested on 6 June 2020 – two days before the Long Bay protest. One of the main demands was accountability for the killing of David Dungay Jnr., who died on 29 December 2015 at Long Bay Prison Hospital. He died repeating the phrase ‘I can’t breathe’ while being pushed down by six guards, including one who held a knee to his back. Dungay Jnr’s killing was reminiscent of that of George Floyd on 25 May 2020 by Minneapolis police, which led to mass BLM protests in the United States.

In response to the Long Bay BLM protest, the Immediate Action Team and riot squad were deployed. They fired tear gas, which was so intense that it contaminated the surrounding neighborhood. The Abolitionist and Transformative Justice Centre Facebook site commented on the risk that tear gas posed to people who were ‘most at risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19’. The Prisoners of Long Bay Jail, in conjunction with prisoners at Metropolitan Remand and Reception Centre (MRRC) Silverwater, released a statement on the force used:

We prisoners passionately embrace the commitment of Black Lives Matter, other organisations and people to force change on the way authorities degrade, attack and kill us.

They stated that the tear gassing on 8 June was ‘standard treatment’. Rather than guards listening, de-escalating or negotiating with prisoners, they were dehumanised and subjected to violent disciplinary tactics.

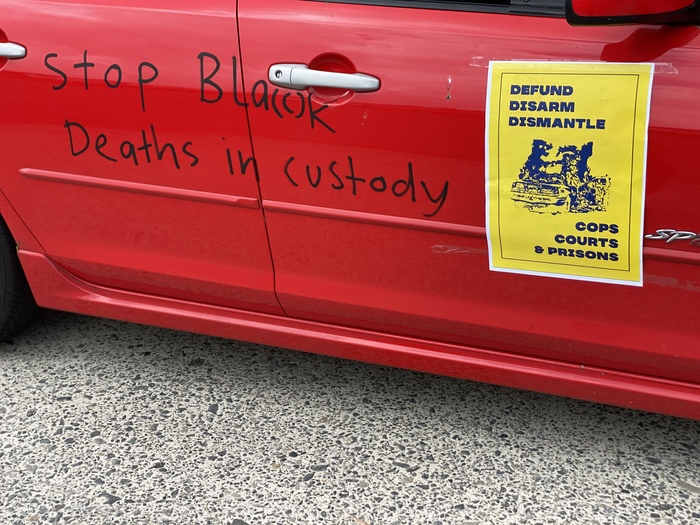

In protest to the conditions at Long Bay, activists staged a car convoy outside the walls of Long Bay prison. On 19 September, signs, chants, and speeches condemned the killing of David Dungay Jnr. and demanded the abolition and defunding of police. Over 100 protesters in the car convoy lent their solidarity to those behind the walls of Long Bay. This was a critical demonstration of the mobilisation inside and outside prisons, which is a necessary congruence for the realisation of abolitionist aspirations.

Abolitionism in the Age of COVID-19

With burgeoning fears of COVID-19 in prisons and resistance to prison and police violence, there has been an upsurge in calls for prison abolition and defunding police. Debates and strategies for carceral abolition have engaged with the COVID-19 circumstances, but also looked beyond the pandemic and prisons to the broader social infrastructure. Abolitionists have denounced coercive policing of COVID-19 orders, which has especially targeted First Nations people, and called for decarceration, healthcare, housing, food and economic security.

Carceral abolition took hold with the Black Panthers in the 1960s (Kelley 2020). This work has been built over several decades through organisations such as Critical Resistance in the US and Sisters Inside in Australia. The pandemic has prompted new contributions to conversations and activism around dismantling prisons as well as amplified the voices of long-standing advocates. Sisters Inside founder and CEO Debbie Kilroy (Kilroy et al. 2013) regards prison abolition as both tearing down prison walls and building bridges in society. In response to the pandemic, Kilroy (2020) described prison as a potential ‘death sentence’ and called for the release of women to ‘safe, secure accommodation, with adequate resources to live’.

A transformative structural approach to abolition is also advocated by key US abolitionists such as Angela Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore. They call for recreating relationships and social structures to abolish ‘the conditions under which prison became the solution to problems’ (Gilmore and Murakawa 2020; see also Davis and Dent 2020). Abolition, according to Gilmore, needs to be red (by communising social structures to provide for the vulnerable), green (by reallocating resources to combat environmental racism) and internationalist (by transcending borders to create a ‘better world’).

In COVID times, however, policy and practice on the part of the state and capital are predicated on ‘organised abandonment’ producing unemployment and neglect (Gilmore and Murakawa 2020) and ‘organised violence’ through policing and punishment (Gilmore 2020). Gilmore implores unity of the abandoned and the violated to resist the dominant structures. For Davis, socialist responses are necessary to rebuild public institutions and counter the prison industrial complex (Davis and Taylor 2020).

The seeds of radical change germinated in BLM movements, including in Australia. These were a product of tensions over coercive state practices such as the prison system and the endemic racism of the criminal (in)justice system. In settler colonies, First Nations organisations called for not only an end to the imprisonment and deaths in custody of their people, but also the reclamation of Indigenous land, the reinstatement of Indigenous values and knowledges, self-determination, and equitable provision of First Nations healthcare and accommodation in place of penal and child protection policies. COVID-19 was one catalyst for renewed thinking about abolition that responded to a range of structural injustices tied together with prison injustice. The pandemic demonstrated that the injustices of organised abandonment and abuse permeate the parameters of the prison and the solutions require community mobilising and support.

Abolition and Decarceration Strategies in the Pandemic

COVID-19 has seen the abolition movement reenergise its efforts through coalition-building and mutual aid. The formation of No Prisons – a Canadian coalition of grassroots organisers, formerly incarcerated persons, activists, academics, and groups such as Free Lands Free People, Black Lives Matter, Migrant Rights Network, and the Center for Gender Advocacy – reflected the need for new ways of organising under COVID-19. In Australia, the #CleanOutPrisons campaign was initiated in 2020 by First Nations families with the support of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services (NATSILS) and Sisters Inside to advocate for decarceration and provide support to people in prison. Broad advocacy alliances formed to demand the release of people from Australian prisons during the pandemic in three open letters. The letters were coordinated by academics, NATSILS, barristers, and community legal services, and reflected open letter campaigns overseas.

In addition to advocacy and campaign strategies, coalitions and grassroots organisations supported people in prisons and coordinated mutual aid. Mutual aid is a form of social infrastructure based on local relationships of care to ensure equitable access to resources and services (Sparrow 2020). Mutual aid is enacted in the work of First Nations and multicultural organisations in Australia, such as Deadly Connections, Nelly’s Healing Centre, and Young Spirit Mentoring Program, which provide food and programs for people in need. Justice Reinvestment in Bourke, NSW, which calls for state funding to be redirected away from prisons and towards building stronger communities, continued to deliver services to First Nations people during the COVID lockdown. No Prisons in Canada supported the local distribution of goods and services, and the CleanOutPrisons campaign in Australia delivered hundreds of bars of soap to prisons to save lives and highlight unhygienic prison conditions.

Pandemic Policy is Not Enough for Abolition

During the pandemic, Australian governments and legal institutions have responded to advocacy and mass protests against prisons (Henriques-Gomes and Visontay 2020). In NSW alone, emergency prison release laws were introduced (although not yet applied), a parliamentary inquiry into First Nations incarceration and deaths in custody was instigated, and the number of people in prisons dropped by 10.7 per cent (BOCSAR 2020).

However, abolition is a project beyond policy. Rebuilding social, political, and economic structures and enhancing infrastructures requires sustained collective action and solidarity-building. It involves humanising abandoned people and developing relationships of inclusion and non-violence. The protest at Long Bay and the subsequent car convoy was part of a solidarity and inclusion movement towards abolition. It linked the resistance and demands of people on the inside with people on the outside. The pandemic has been a stage for unifying and expanding decarceral strategies and the challenge is now to enliven them.

Works Cited

BOCSAR [NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research]. 2020. ‘Media Release: NSW Custody Statistics: Quarterly update June 2020’.

Caruana, Catherine. 2020. ‘COVID-19 and Incarcerated women: a call to action in two parts – Part Two’. Centre for Innovative Justice RMIT. 8 May.

Davis, Angela Y. and Dent, Gina. 2020. ‘Visualizing Abolition with Angela Y. Davis and Gina Dent: an online conversation’. UC Santa Cruz Arts, Lectures and Entertainment. 21 October.

Davis, Angela Y. and Taylor. Astra. 2020. ‘Angela Davis on the Struggle for Socialist Internationalism and a Real Democracy’. Jacobin. 31 October.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. 2020. ‘The Case for Prison Abolition: Ruth Wilson Gilmore on COVID-19, Racial Capitalism & Decarceration: A discussion with Amy Goodman’. Democracy Now. 5 May.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson and Murakawa, Naomi. 2020. ‘Ruth Wilson Gilmore on Covid-19, Decarceration, and Abolition: How should abolitionists respond to the coronavirus pandemic?’ Ruth Wilson Gilmore, in conversation with Naomi Murakawa for Haymarket Books. 17 April.

Henriques-Gomes, Luke and Visontay, Elias. 2020. ‘Australian Black Lives Matter protests: tens of thousands demand end to Indigenous deaths in custody’. The Guardian, 7 June.

Kelley, Robin D.G. 2020. ‘What abolition looks like, from the panthers to the people’. Medium. 26 October.

Kilroy, Debbie. 2020. ‘Death sentence for poverty? Why the over-representation of First Nations women prisoners matters during the pandemic’. Australian Lawyers Allliance. 27 May.

Kilroy, Debbie et al. 2013. ‘Decentring the prison: abolitionist approaches to working with criminalized women’. In Women exiting prison : critical essays on gender, post-release support and survival. Carlton, B. and Segrave, M. Abingdon (eds): 338–387. New York: Routledge.

Londoño, Ernesto et al. 2020. ‘As Coronavirus Strikes Prisons, Hundreds of Thousands Are Released’. New York Times, 26 April.

Patterson, Orlando. 1982. Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Price, Joshua. M. 2015. Prison and Social Death. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Saloner, Brendan et al. 2020. ‘COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in Federal and State Prisons’. JAMA. 324(6): 602–603.

Sparrow, Josie. 2020. ‘Mutual Aid, Incorporated’. New Socialist. 23 April.

Tang, Helen and Corben, Simon. 2020. ‘Statistical Publication No. 48: NSW Inmate Census 2019 – Summary of Characteristics’, Corrective Services NSW.