Andrew Brooks, Astrid Lorange, Liam Grealy

March 2021

Where life is precious, life is precious.

— Ruth Wilson Gilmore

The world has been plunged deeper into a state of crisis by the global spread of COVID-19. In 2020, the pandemic brought with it a death toll that continues to climb, as well as border closures, travel bans, social isolation, a redefinition of socially necessary work, and the onset of a global recession. We find ourselves confronted by compounding crises that can be traced, in the global north, to the 1970s, and which are visible as mass deindustrialisation, the erosion of the welfare state, wage stagnation and rising unemployment, and massive wealth disparity. Crisis, as Stuart Hall and Bill Schwartz tell us, ‘occurs when the social formation can no longer be reproduced on the basis of the pre-existing system of social relations’ (Hall 1988, 96). The pandemic has brought into sharper relief the existing infrastructural inequalities endemic to the constellation of crises that define the last forty or so years of liberal capitalism and that appear, at this point, as if the norm. The unequal distribution of access to the resources and networks of subsistence and care necessary for living has resulted in increased risk of exposure to the virus and vulnerability to death. It comes as no surprise that the distribution of access to infrastructures such as healthcare, housing, clean water, education, and safe working conditions – exacerbated by COVID-19 – is unjustly refracted along race, class, and gender lines.

One response to this unprecedented global health crisis from governments around the world has been the intensification of policing. In Australia, a state of emergency was declared in Victoria as the number of COVID-19 cases steadily climbed, with police and protective services officers mobilised to enforce state government-mandated lockdown restrictions (McDonald, this issue). From 17 March until 24 August, Victorian police issued 19,324 COVID-related fines, totalling more than $27.8 million in revenue. While the bulk of these fines remain unpaid, suggesting frustration with the law-and-order response to the pandemic, they are but one example of the centrality of policing to crisis management.

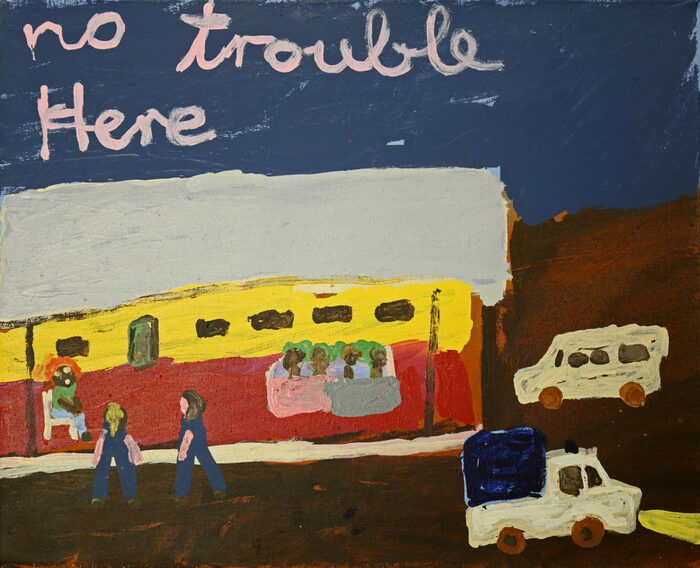

On 4 July 2020, hundreds of police officers were deployed to nine public housing towers in the inner-city Melbourne suburbs of Flemington and North Melbourne to secure the buildings and enforce a lockdown of its inhabitants. The stated justification for the police presence and lockdown of residents was the risk of potential spread of COVID-19 in the high-density buildings. The ‘hard lockdown’ of the towers meant that roughly 3,000 people were forbidden from leaving for any reason. The restrictions lasted for five days at the Flemington towers and 14 days at the North Melbourne estate. Residents of Flemington and North Melbourne living in owner-occupied housing, including similar-sized private apartment complexes, were not subject to the same lockdown measures and could leave home for the four reasons specified in the Victorian Government’s stage three restrictions: shopping for food, exercise, work or education, and medical care or caring responsibilities. This uneven deployment of state power produced a media spectacle in which the policing of largely low socio-economic and migrant public housing residents was posited as decisive government action. Community organisations and mutual aid networks – both incorporated and informal – responded immediately to the policing of the public housing towers. Food deliveries, baby formula, nappies, sanitary products, and other essential items that were suddenly inaccessible to residents were crowd-sourced and delivered (provisions supplied by the Government following the immediate, hard lockdown were inadequate and contained expired food stuffs). Residents inside the towers organised as a collective called Voices from the Blocks, communicating their opposition to detention through a range of media and issuing a set of demands to the Victorian Government.

The policing of the towers obscured the structural and infrastructural neglect of public housing that has taken place over the longer term and that has resulted in the overcrowding of apartments, poor natural ventilation and centralised airflows, and a reliance on shared spaces and facilities – all factors that increase the risk of the coronavirus spreading. The systematic erosion of public spending on housing and social infrastructures designed to support those on low incomes or recently arrived migrants has left such people vulnerable to state-sanctioned discrimination, intensified policing, and death (Carrasco et al. 2020). What we saw in the Victorian Government’s handling of the public housing towers lockdown is the intertwined relationship between infrastructural inequality, policing, race, and class.

In the United States, as the spread of the virus reached uncontrollable levels and amidst widespread shelter-in-place orders, the infrastructure of policing and the carceral apparatus that accompanies it was called most forcefully into question by mass struggle. In the wake of the murder of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis, Minnesota on 25 May 2020, protests and riots irrupted in the streets. The death of yet another Black person at the hands of police was the tipping point that ignited a wave of uprisings: thousands of people marched, police precincts were burned to the ground, mass looting and the destruction of commodities took place, autonomous zones were established, and communal infrastructures enacted.

The uprisings took aim at the systems, structures, and infrastructures central to the perpetuation of racialised violence and inequality: private property, police, prisons. They were a strike against the anti-Blackness that underpins US imperialism; at once an expression of rage, refusal, and survival. The language of abolition grew louder each day. ‘No justice, no peace, no racist police’ rang through the streets and online organising spaces. The chant of ‘care not cops’ announced the popular take-up of abolitionist feminisms, which have long argued not only for the dismantling of the police and the carceral state but, crucially, for the building of alternate infrastructural forms that can support and sustain life rather than discipline and extinguish it. As Ruth Wilson Gilmore (2020a) puts it, ‘abolition is not the absence of something; it’s the presence of something’ (170). It is a reorientation from the apparent inevitability of the prison and police to the conditions that underpin the policing and prison industrial complexes and the potential to combat them (Davis 2003). While it is too soon to know what will come of these uprisings, the ongoing struggle – coupled with the emergence of widespread rent strikes and large-scale labour organising across the world – appear to announce a collective demand that everything must change.

The widespread and disparate actions that gathered under the banner of Black Lives Matter were not limited to the US and quickly took on an international character with the organisation of solidarity actions and protests across the world. In Australia, where Blackness and Indigeneity come together, the mass protests that took place in June and July were simultaneously expressions of solidarity with the US uprisings and resistance to the racial violence of policing and incarceration in local contexts. Three decades after the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody handed down its report in 1991, there have been at least 437 more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander deaths in custody. The death of Dunghutti man David Dungay Jr. while he was incarcerated in Sydney’s Long Bay Correctional Complex on 29 December, 2015, forges a direct link with the murder of George Floyd. Dungay Jr., a diabetic who was insulin-dependent, was violently restrained by prison guards who stormed his cell after he refused to stop eating biscuits. Dungay Jr., like Floyd, was captured on video repeating the utterance ‘I can’t breathe’ over and over again. His plea, too, fell on ears that refused to listen. While Dungay Jr.’s death forms the most direct comparison, the killing of First Nations people by the state is a recurring event in the Australian settler colony, and the protest actions that emerged across the country invoked the names of Kumanjayi Walker, Aunty Tanya Day, Ms Dhu, Nathan Reynolds and many others. The protests saw thousands of people gather across the country, with many mobilising around the call to abolish the police and the carceral system. If the responses to the lockdown of Melbourne public housing towers constitutes the making of power, for Gilmore (2007) then, the ongoing intensity of distributed and multi-issue organising in Australia over the past year signals the way that ‘movement happens’ (248).

What is abolition a call for? And how does it relate to the question of infrastructure? Here we are following a well-established Black radical internationalist tradition that sees abolition as an ongoing and revolutionary project rather than a static endpoint. Abolition moves beyond calls to simply reform prisons and policing, positing that an end to structural racism and state violence requires upending the political, economic, and social conditions that produce them. Put more directly, abolition is a form of revolutionary anti-capitalist struggle. A crucial part of the revolutionary agenda of abolition is to intervene in the reproduction of existing inequalities and to build material infrastructures and networks of care that support people’s needs before they find themselves in precarious situations. For Gilmore (2020b), one of the key questions driving abolition is: ‘What are the conditions under which it is more likely that people will resort to using violence and harm to solve problems?’ But diagnosis is not the end game for abolitionists and so she also asks: ‘What can we do about it so that there is less harm?’ Put another way, what can be done to ‘unravel rather than widen the net of social control through criminalization’ (Gilmore 2007, 242). To which Gilmore (2020b) offers the following as a starting principle: ‘where life is precious, life is precious.’ For Gilmore, this ethos runs counter to the principles that underpin liberal democracies, which are built on a paradoxical understanding of ‘freedom’ that is inextricable with dispossession, punishment, and bondage. The US settler colony, the context Gilmore is writing about, was founded on the dispossession of Indigenous people and the enslavement of Black people, twin forms of subjugation that are reproduced today as social and actual death. To take seriously the claim that life is precious is to work toward building new conceptions of justice and care that do not reproduce carceral logics, the central premise of which is the differential valuation of life.

Abolition seeks the transformation of the world, but it is not content to wait for a world-historical revolutionary rupture. It is also a practice that intervenes in existing inequalities by building and organising alternative social infrastructures that facilitate and gesture to ways of living outside the racial capital relation. Angela Y. Davis (2020) puts it like this:

Abolition is not primarily about an end to be achieved, but rather about how we conceptualise social justice issues as always interconnected and interrelated. We do not focus myopically on a single issue – say the institution of the prison – and we do not seek single and isolated solutions, but rather ask what needs to be changed about the larger society, so that we no longer rely on institutions that reproduce the very violence that they are supposed to minimise. So how would we imagine a society without prisons and without institutionalised police violence? This would entail reenvisioning not only justice and security, but also economic structures, education, healthcare, and so on. Justice that helps us transform social relationships, and security that acknowledges what it really means to feel safe, would require revolutionary change. (215)

The protests and forms of resistance that we have seen across the world in 2020, and that we gesture to above, all rely on various forms of infrastructure: from interfacing with settler legal systems to obtain permits to protest and with the digital systems of big tech to organise, to the sound systems used to amplify dissent and the manufacture and distribution of hand sanitiser and face masks to ensure that protest remains COVID-safe (Anthony, this issue). Such engagements with infrastructures are never clearly captured by racial capital logics nor are they necessarily revolutionary, but their intents and intensities provide moments that enable abolitionist solidarities to emerge and resistance to flourish. In these moments, we might find hope in the promise that a different world is possible.

Our interest expands from the street to the sites of infrastructural inequality that we explored in Issue 1 of the Infrastructural Inequalities journal: housing, water, waste, paperwork, data, and energy. We are interested in the possibilities of building public and communal infrastructures without reproducing the policing functions that have come to permeate many of these institutions (Curtin, and D’Souza, this issue). In this we are fortunate to have numerous examples to draw from and guide us. We take inspiration from the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense’s police patrols and Free Breakfast for School Children Program (the latter which former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover saw as a considerable threat for its contact with and community-building around young Black people). We look to the Black power activism of Redfern in the late 1960s and ’70s that saw the establishment of Aboriginal-run social welfare infrastructures such as the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs, the Redfern Aboriginal Legal Service, and more (Foley 2001). We look to the internationalist network of abolitionist organisations working to develop infrastructures and mutual aid networks that minimise the impact of policing on those who are systematically policed, such as INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence, Sisters Inside, Rise: Refugees, Survivors and Ex-detainees, and Critical Resistance.

This issue of Infrastructural Inequalities seeks to investigate how crisis, policing, and infrastructure are bound to each other. In turn, it asks how an abolitionist approach to infrastructure might move us toward a world in which the needs of all are met. This would require an approach to both abolition and infrastructure that is, as Gilmore (2020b) puts it, green, red, and international:

[A]bolition has to be “green.” It has to take seriously the problem of environmental harm, environmental racism, and environmental degradation. To be “green” it has to be “red.” It has to figure out ways to generalize the resources needed for well-being for the most vulnerable people in our community, which then will extend to all people. And to do that, to be “green” and “red,” it has to be international. It has to stretch across borders so that we can consolidate our strength, our experience, and our vision for a better world.

The following issue features original work on questions of crisis, policing, abolition, and infrastructural inequality by Thalia Anthony, Farhad Bandesh, Johanna Bell, Rocket Bretherton, Andrew Brooks, Gabriel Curtin, Sab D’Souza, Liam Grealy, Debbie Kilroy, Tabitha Lean, Astrid Lorange, Dave McDonald, Stella Maynard, Farhad Rahmati, and Mark Steven. This work examines prison protest, storytelling, thermal violence, mandatory detention, public and online policing, and other issues through different valences of an abolitionist politics. We are excited to present the second issue of the Infrastructural Inequalities journal and hope that it contributes to discussions and organising around abolition and infrastructural inequalities.

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Steaphan Paton, Therese Ritchie, Sally M. Nangala Mulda, and Tim Gregory for so generously allowing us to illustrate this essay with their works.

Works Cited

Carrasco, Sandra, Faleh, Majdi, and Dangol, Neeraaj. 2020. ‘Our Lives Matter – Melbourne Public Housing Residents Talk About Why COVID-19 Hits Them Hard.’ The Conversation. 24 July.

Davis, Angela Y. 2003. Are Prisons Obsolete? New York: Seven Stories Press.

Davis, Angela Y. 2020. ‘Abolition Feminism: Angela Y. Davis.’ In Brenna Bhandar and Rafeef Ziadah (eds). Revolutionary Feminisms: Conversations on Collection Action and Radical Thought, 203-215. London and New York: Verso.

Foley, Gary. 2001. ‘Black Power in Redfern 1968-1972.’

Hall, Stuart. 1988. The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left. London: Verso.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. 2020a. ‘Abolition Feminism: Ruth Wilson Gilmore.’ In Brenna Bhandar and Rafeef Ziadah (eds). Revolutionary Feminisms: Conversations on Collection Action and Radical Thought, 161-178. London and New York: Verso.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. 2020b. ‘Ruth Wilson Gilmore Makes the Case for Abolition.’ The Intercept. 10 June.

Mussa, Najat. 2020. ‘Housing estate lockdown: What happened to ‘together’?’ The Age. 6 July