Sab D’Souza

March 2021

The Women of Colour (WOC) Web was an autonomous Facebook group for women and non-binary people of colour. It offered a safe alternative to other, typically white, feminist spaces on and offline. What started as a single group grew into an ecosystem of subgroups that sprouted from the diverging aspects of its members’ identities. At its peak, The WOC Web had over 3000 members from across ‘Australia’, which fluctuated throughout its five-year operation.

I joined in 2013 and was exposed to a language that described what I had always known viscerally. I opened up to others who, in turn, opened themselves up to me – this intimacy rewarded us with a profound pleasure in each other’s digital proximity. Sara Ahmed (2014) describes queer pleasure as a specific feeling that erupts when one refuses to comply with the dominant scripts of heterosexuality. In a sense, our pleasure was produced through our refusal to comply with the dominant scripts of whiteness. If I passed a member on the street, at a protest, at the pub, or across campus, we would steal a glance and smile.

However, in 2017, following a string of privacy breaches and mounting tensions between admins and users, the network was abruptly deleted. In 2019, I sat with six former members of The WOC Web to reflect on the group and its deletion. In this essay, I describe the group as predicated on a culture of risk and safety management, an online space which employed the logics and practices of policing to an already marginalised user base. At the same time, this group was my formative foray into peer-led activism and research.

My engagement with participants followed a call-out that was circulated online. Ninety-minute, semi-structured interviews took place in person and by video call. Interviews were structured according to various topics, including participants’ relationships to their racial and gender identity growing up in Australia and their experiences in The WOC Web and other digital spaces. Participants’ roles within the group varied: some were part of the original admin team; some were dedicated members while others were less active.

In the following analysis, I use qualitative accounts of the group and its practices, alongside analysis of Facebook’s algorithmic infrastructure, to reveal how the vocabulary of policing was felt by members and enforced through Facebook’s interface. Through this analysis, I reveal the harmful impacts of punitive measures taken up under the auspices of safety. Reflecting on such measures and their impacts is especially important as peer-led initiatives continue to use social media platforms in efforts to organise, protest, and provide care for one another. By examining Facebook’s group infrastructure, we can see how the logics of policing are inscribed into our digital collectivising. Facebook groups dedicated to mutual aid, rough trade, or paying it forward are spaces that allow us to come together yet often expose us to harm.

Facebook positions itself as a platform designed to reconnect users with people they already know. To aid in their efforts, Facebook requires its ‘community’ use their legal name, which is then verified through government-issued identification, photos (contributing to a growing database of facial recognition), and other information that is now typical of ‘public by default’ social media (boyd 2010, cited in Cho 2017, 3184). Facebook’s algorithms rely on this data to emulate users’ offline encounters, recreating intimate networks through its predictive content visibility structure.

Facebook uses both humans and AI to detect and remove posts that violate its content policy. However, human moderation is routinely outsourced to contract labour to cut costs and mitigate liability. Employees of these third-party arrangements are incentivised through speed-based metrics, and global-scale policy discourages employees to consider the specific contexts in which content may or may not be harmful. We know little about the details of Facebook’s moderation policies, which are loosely outlined under Facebook’s Community Standards. These standards play a part in a larger strategy that Facebook and other platforms employ to ‘straighten’ digital spaces to a universal (and US-determined) standard and, as such, are important to marketability and profitability. Digital platforms can even encourage users to participate in these safety policies by allowing them to report their peers’ content (e.g. reporting another user’s name as false).

These policies largely impact already vulnerable people (Black, brown, trans, queer, and disabled digital creators), as seen in the erasure of sex workers online through the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act and the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act and the Allow States and Victims (FOSTA-SESTA)(2018/US) in which a law established obligations on US-based platforms to censor their users presumed to be sex workers. While the internet can be an invaluable tool for vulnerable users to mitigate harm, moderation policies attempt to standardise the behaviours of their global user base under the guise of safety. These impacts are not distant concerns, as made evident by sex workers in ‘Australia’ who warn the upcoming Online Safety Bill will have a similar devastating impact on our digital communities (see also FreeBasics program in Myanmar, and India).

While still subject to these standards, Facebook groups are considered socially moderated spaces. Members are expected to adhere to the group’s code of conduct, stipulated and managed by its admin/s. As a self-identified safe space, The WOC Web’s policy and posting guideline was publicly visible and briefly outlined to prospective members in the ‘about’ section (e.g. no anti-Blackness, no fatphobia, no whorephobia, apply trigger warnings, etc.). A separate, detailed document was only visible to members after they were accepted. New members were asked to comment beneath this document to signal that they had read it and agreed to the group’s terms. The safe space policy was not a static set of rules but changed to reflect various conflicts and shifting concerns that members held. Interview participants referred to the safe space policy as a responsive document that was updated ‘in real time’, mostly in accordance to how admins maintained the group’s identity as a ‘safe’ autonomous collective.

Feeling Safe – Platform Affordances Towards Safety

In the beginning, The WOC Web grew by invitation. Any user could request to join, and people invited by existing members were instantly accepted, which allowed the group to rapidly expand from its core membership. In 2014 this changed after a series of self-identified white users began to seek access to the space. In one instance, a white user was added to a subgroup by another member. The user made a post stating she knew she was not meant to be in the group but hoped she could stay because she was an ally and wished to share job opportunities. Members argued that although well-intentioned, her presence was a threat to group members’ safety. A few months later, a different white user posted, stating that she had been documenting evidence of the group’s ‘reverse racist’ practices and was going to create a documentary exposing everyone involved. It was during this time that admins and members began to discuss a need for stricter policies to ensure that the group’s autonomy would remain intact. Admins changed the group setting to ‘private’ and began messaging prospective members about their racial identity prior to joining.

In late 2016, a few months prior to the group’s deletion, this policy was changed again. Admins required all pending members to be ‘vouched for’ by an existing member. These changes were contentious – some felt these policies were a necessary security measure, while others felt that this ‘gatekeeping’ replicated the harms they had experienced elsewhere. Facebook has since implemented practices similar to those used by The WOC Web admin team. In the past, The WOC Web privately messaged prospective member admission questions before allowing them into the group. Now, Facebook allows admins to set up automatic questions that they are prompted to answer. These changes to Facebook groups demonstrate how risk management strategies are continuously reworked into the digital interface and the way that platforms extract value from user behaviour.

Admins were also expected to manage the various discussions between members. Facebook supports admins in their role through technical affordances (or admin privileges), which allow admins to govern other members’ behaviour (Cirucci 2017). Technical affordances do not simply govern usability but are relational and shape social behaviour. When appointed as an admin, the user is granted an arsenal of tools to enact punitive power. An admin’s authority is demonstrated in their capacity to restrict what others do, often in the name of upholding safety. Examples of this include restricting a member’s posting privileges, closing a discussion thread, banning/deleting members, and pinning posts to the top of the News Feed. These actions seek to secure a group from perceived threats through disciplinary measures. In this way, Facebook groups and the platform itself are organised, as Jackie Wang (2020) asserts, though the ‘spatial politics of safety’ (270). In The WOC Web, members were allowed to move relatively freely within the group as long as they did not impede on the admins’ conceptualisation of safety. This stood in constant tension with the group’s desire for ‘moral dialogue’, which was fraught with conflict, difficult disclosures, and big feelings. As Ev, a founding member of The Women of Colour Web, reflects:

It was a difficult space to navigate because you can’t have a safe space, and also have each post detailing something traumatic. Because people don’t get the choice to engage with that sort of content.

Members like Ev noticed a trend in such messages posted to the group by new members. These posts were dismissed with comments for the OP (Original Poster) to ‘educate’ themselves using the search function.

Often these posting faux pas were made by members who did not share the same social networks and therefore the social and cultural capital as older members. As one member, Siobhan, described her experience:

But the thing with those spaces is you actually need to build social capital for you to like get any traction, and because [new members] weren’t familiar with my name or my face, and I look like a weird white bitch, I had no social capital.

New members’ inexperience or lack of social connection through Facebook further marked them ‘risky’ to the imagined social cohesion of the group. As a result, posts by members already on the outskirts of the network were frequently the cause of social discord and were readily removed by admins.

Admins’ technical capabilities shaped the behaviour of members in accordance with the group’s policies, but also were reflective of the dominant social norms of the most active members. What one admin might consider a generative discussion another could just as easily be determined harmful. Typical of activist spaces, safe space language was employed by both admins and members of The WOC Web, often conflating personal discomfort with imminent danger. Wang (2020) suggests that phrases of personal sentiment are overly used in activist safe spaces precisely because they ‘frame the situation in terms of personal feelings, making it difficult for others to respond critically’ (282). The WOC Web was founded on the basis of its original members’ exclusion from white feminist spaces; notably, these spaces also frequently employed safe space language to discredit POC members’ criticisms of the white majority. As Ev noted, this behaviour was restaged within the new network:

The groups were seen as a safe space, so when conflict arises inside that group… it hurts more. Because white feminism is something that happens externally, it’s almost water off a duck’s back because we expect it. But in [The WOC Web] it was lateral violence and anti-Blackness. So yeah, those discussions destabilised the sort of safety and security that we wanted to feel.

Though discussion was encouraged between members, if a thread got too big due to a conflict, admins would intervene by turning off comments. Siobhan described these moments as ‘quite A versus B. It’s not collaborative, there’s no interjecting and it feels quite aggressive.’ Admins had to rely on their personal judgement, drawing upon their lived identities alongside the responses from the group signalled through likes and comments. This tactic tended to favour ideas held by members most socially intertwined with one another. Admins used digital affordances to mitigate risks to the social cohesion, and therefore safety, of the group. However, Facebook’s editorial practices, particularly its content curation algorithm and interface design, inferred admins’ power through a hierarchy of visibility.

Feeling Seen – Algorithms and Surveillance by Design

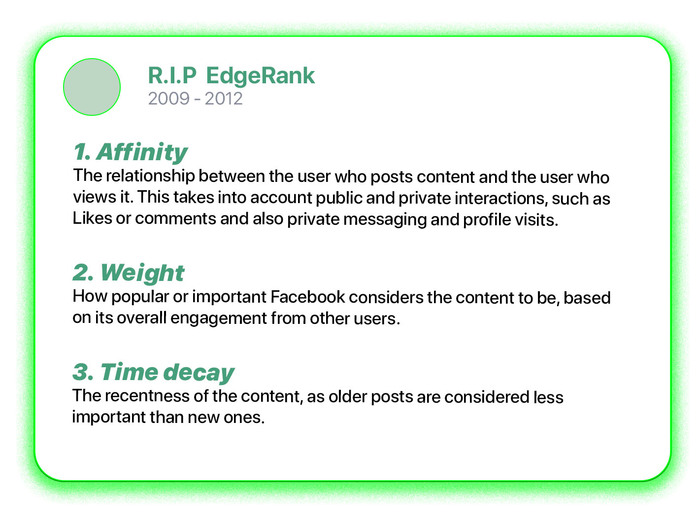

Between 2009 and 2012, Facebook used the content-sorting algorithm EdgeRank for its News Feed. EdgeRank scored content across three areas (affinity, weight, and time decay) to determine preference order. Facebook then replaced EdgeRank with a machine learning system, asserting that its core factors were still taken into account along with over 100,000 others. Facebook’s propriety algorithm remains closely guarded, unnamed and relatively obscured to the public. While its obscurity safeguards the function from theft, it simultaneously makes difficult work for the digital researchers who attempt to trace its harmful social impact (see Munn 2020 and Matamoros Fernádez 2017). Automated systems are frequently designed to identify and predict ‘risk’. These often discriminatory design processes use past data to determine how to make choices in the future. As Safiya Noble (2018) argues, algorithms are not impartial choice-making machines, but rather act out the unconscious bias of their creators. Ruha Benjamin (2019) writes that these automated systems are the new Jim Crow (which she refers to as the ‘New Jim Code’) in their capacity to reproduce racial inequality – such as the investigation by ProPublica into Facebook’s advertising affordances which allowed companies to specify whether Black people could see their real-estate ads – or gender inequality – as Amazon’s recruiting AI discriminated against women applicants. These systems are imbued with the social norms of the white, cisgender, male demographic that governs Big Tech.

In 2016, a year prior to The WOC Web’s deletion, Facebook introduced the ‘Stories from Friends’ update. ‘Stories from Friends’ aimed to give additional visibility to a user’s close friends and family. The restructuring of Facebook’s content algorithm anticipated higher engagement by predicting users’ intimate networks. This update impacted the social infrastructure of Facebook Groups. As Juul (former admin) aptly stated: ‘Fuck that algorithm!’ After the update, Juul began to notice more posts from members who had close digital relationships with other admins (such as being Facebook friends, private messaging, and other interactions with them on the platform). From my perspective, this contributed to a feeling of surveillance, empowering admins in their role through what Michel Foucault (1995) terms ‘permanent visibility’ (196). Whenever an admin interacted with a post, that content would be prioritised and sent to the top of the members’ News Feed. Admins were highly visible within the space, especially as they were uniformed by Facebook through the tiny cop badge next to their names. As members’ visibility in the network became contingent on admins’ recognition, some sought – perhaps unconsciously – to build an alliance. Members were observed liking or bumping an admin’s post or tagging an admin in the comment section to demonstrate their connection to the space. This also had the effect of granting them greater visibility. I’ve termed the latter ‘corrective commenting’, a practice particularly encouraged by admins as one member Mari recalls:

They [admins] always thanked people who commented or pointed out problematic members’ posts. I think because of that, the rest of us felt involved. Like if I saw a post that broke the rules, I’d try and explain first. We’d do that sort of work before mods were called in as much as possible. Because we knew they appreciated and acknowledged our labour.

The most commonplace example of corrective comments in The WOC Web was around the use of content warnings. Posts with potentially triggering content were expected to be ‘nested’ behind a series of characters, and appropriately titled (e.g. ‘CW: fatphobia, discussion of food’).

If a member failed to nest their post and/or flag it appropriately, users would quickly highlight the mistake, asking them to edit or remake the post. However, members would often repeat the correction, until either the issue was fixed, the post was deleted, or an admin was tagged. When an admin eventually came online, they would respond by thanking and liking the comments of the users who had corrected the original poster and close the thread. Participants recalled admins frequently asking members to ‘correct’ mistakes of new members when the admins were offline. ‘Corrective commenting’ was thus used to extend the admins’ presence beyond their active duty and was thought to be a mutually beneficial practice where members helped others ‘learn’ the rules whilst gaining a greater sense of belonging.

To frame this within the symbolism that Facebook provides, members endeavoured to demonstrate they were law-abiding citizens by pointing out how others were ‘problematic’. This in turn imbued members with a greater sense of belonging to not only the group but to each other, with harmful consequences. While digital infrastructures deploy punitive logics through algorithmic functions, attention should also be given to collectives who re-perform this ‘gleeful othering, revenge, or punishment of others, particularly when these things deepen our belonging to each other, usually briefly, until we too fuck up’ (brown 2020, 12).

Siobhan observed that the peer-based learning space was superseded by these determinations of guilt: ‘you had to be proven innocent.’ By framing others as guilty, members could align themselves as ‘good’. This meant that users who broke the rules – either by choice or honest mistake – faced an onslaught of corrective comments. Members who critiqued the practice as ‘unproductive’ and harmful were interpreted as attacking a hierarchy of control that kept good members safe. Newer members began posting less, and the most vulnerable members (those with smaller social circles, and less robust connections to the group) likely stopped all together. Aafia (admin of a subgroup) claimed that corrective commenting harmed the group’s culture as a learning space – ‘having a thousand [corrective] comments on a thread is just not meaningful dialogue’.

It is unproductive to write off virtual spaces like The WOC Web as simply ‘community done wrong’. By placing blame solely on admins’ or members’ actions we further obscure the structural prejudices present within our digital platforms. When moderators of Facebook groups are presented as the only measure to secure safety, we mask the fact that Facebook is the constituent mechanism through which these unsafe acts are empowered and carried out. This in turn restricts how we envision digital communities free of these devices in the future. Like a CCTV camera with a post-it note reading ‘SMILE YOU’RE ON CAMERA!’ our current infrastructure relies on surveillance to manage users’ behaviour regardless of whether the camera is unplugged or the mods are asleep.

Works Cited

Benjamin, Ruha. 2019. Race After Technology. Hoboken: Wiley Press.

Blunt, Danielle. and Wolf, Ariel. 2020. ‘Erased: The Impact of FOSTA-SESTA & the Removal of Backpage’. Anti-Trafficking Review, 14: 117-121.

brown, adrienne maree. 2020. We Will Not Cancel Us: And Other Dreams of Transformative Justice. Chico: AK Press.

Cho, Alexander. 2017. ‘Default publicness: Queer youth of color, social media, and being outed by the machine’. New Media & Society, 20(9): 3183-3200.

Cirucci, Angela M. 2017. ‘Normative Interfaces: Affordances, Gender, and Race in Facebook’. Social Media + Society, 3(2): 1-10.

Foucault, Michel. 1995. Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books.

Matamoros-Fernández, Ariadna. 2017. ‘Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube’. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6): 930-946.

Munn, Luke. 2020. ‘Angry by design: toxic communication and technical architectures’. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1).

Noble, Safiya. 2018. Algorithms of oppression: Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: New York University Press.

Wang, Jackie. 2018. Carceral capitalism. California: MIT Press.