Dean Cross, Andrew Brooks, and Astrid Lorange

November 2019

Dean Cross grew up on a farm in Ngunnawal/Ngambri Country. He is of Worimi descent. Cross worked as a dancer and choreographer for more than a decade before moving into installation, sculpture, and photography. His work often engages with national and archival histories, text, and infrastructural systems. He has a particular interest in the raw materials that are extracted, produced, and distributed by large-scale industrial projects – the nation-state, for example.

We met Cross at Cafe Ella in Darlington on 17 July 2019. We had our baby with us. She had recently turned one and spent the entire time crawling, cruising, squealing, and flinging cutlery across the table. Dean graciously gifted her a banana and chatted to her throughout; the conversation was punctuated by her digressions.

We wanted to chat to Cross about the work he made for the exhibition Infrastructural Inequalities, staged at Artspace in October of 2018. The exhibition featured work by Cross, the Karrabing Film Collective, and Jack Green, and explored the complex histories of infrastructural projects in the settler colony of Australia – the expropriation of land and the bureaucratic networks that infrastructures such as mining, hydroelectricity, and industrial agriculture depend on.

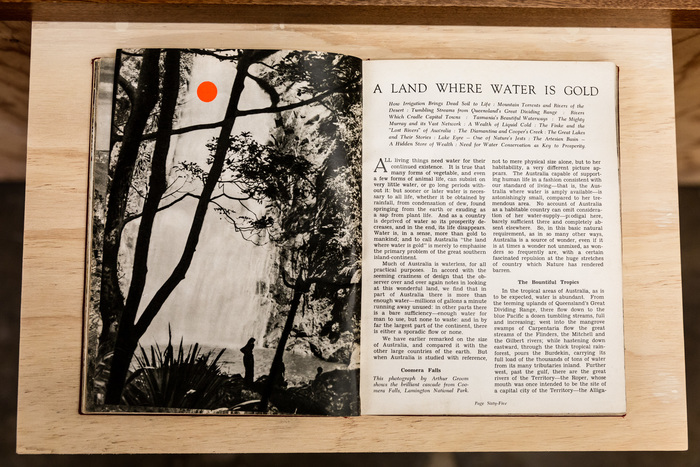

For the exhibition, Cross produced a body of work that took a found object – the hardcover book Wonderful Australia in Pictures (1949, Colourgravure Publication) – as its source material. The book comprises a collection of post-WWII Australian industry and infrastructure, celebrating the achievements of hydroelectric power, suburbanisation, agriculture, and railways. One chapter is dedicated to ‘The Vanishing Aboriginals’, locating First Nations people and culture firmly in a past incompatible with the vision described in the chapter ‘The Wonderful Future Ahead’. This conception of First Nations people as belonging only to the past is, as Maddee Clark tells us, ‘one of the central fantasies of colonisation’. This fantasy affirms the idea of settlement as part of an inevitable march of Enlightenment progress.

Cross installed Wonderful Australia in Pictures in the gallery space, open at a spread. Throughout the book he inserted fluorescent orange stickers (the kind often used by galleries to denote an art work’s sale), transforming particular pages into sculptural objects. The other works, DRILLIN’ & PUMPIN’ and DAMN take images from the Wonderful Australia in Pictures (drilling at Iron Knob mine in South Australia; workers building a dam), reproducing them in large-scale as prints on Australian cotton canvas, layered on wool felt and backed by cotton which had been dyed pink by Roundup – the weedkiller produced by Monsanto. These prints, suspended in the space by thin wire and fish hooks, gently moved like odd flags. Cross’s interest in the specificity of materials (this book, this cotton, this wool, this herbicide, this shade of orange) is part of a larger interest in thinking through the social, political, and cultural histories of Australia by working with real, tangible stuff. ‘I kind of believe in some sort of residual resonance in something that’s real’, he said.

‘I think a lot about stories’, Cross told us as we sat down in the courtyard of the cafe. He went on to explain that his work is motivated by an interest in fictions that appear as facts. The most notable example of this in Australia is the legal fiction of terra nullius: ‘I grew up, as we all probably did, in a “discovery story” kind of version of Australia’, he said. His work mines these colonial narratives for their inconsistencies, scratching the surface to reveal counter-histories hidden beneath. During the interview, Cross told a number of stories about art, family, work, land, and history. Common to his stories was an attention to the way perception is paradoxically easy to shift and yet so often unchanging – it is not difficult to look differently. Yet for the most part, thinking remains committed to its habits, set in its narratives.

Cross spoke to us of working with archives as a way of revisiting and challenging colonial narratives. ‘I think that almost every Indigenous artist at some point has worked with an archive or works with an archive. . . It’s an obvious thing because we’ve been left out of it for so long, or because it’s been mediated in a certain way and so there’s all this “undoing” to do with that.’ He went on to explain that intervening in the archive is always a temporal intervention, an intervention into the fact that ‘we all live in colonised time’. ‘We all live in Greenwich Mean Time’, he said – ‘the whole world has been colonised in that sense.’ Working in the archive then, is a way to ‘un-do or reinsert a narrative – put yourself back into [it]’. One way this intervention can take place, he suggested, is through digital networks:

when you think about pre-colonial story-telling [practices] which were vastly connected and complicated, that were held internally and orally, but were also outsourced in the community where you had a few people who were the holders of different stories . . . it wasn’t one person who held every story but all of the stories in a community – bits were held here, bits were held here, bits were held here, and then through the telling, they would come together. Bureaucracy took us away from that but I think maybe the computer and the internet might be bringing us back to that.

Throughout the interview, Cross returned to the family farm – a space that is both familiar and inextricably linked to a history of colonisation:

The farm’s a weird thing. I’m really interested in farming fences. For me it’s like this perfect colonial narrative. . . Our property, for example, we’re on 200 acres. And I can walk like due north for example. And then for ten, fifteen minutes I’m on ‘our’ land. And then to this fence which is nothing, it’s just a few bits of barbed wire and some star pickets. But it might as well be a hundred-foot big wall, like in Gaza. Because it’s impenetrable. . . . And I really like that kind of weird shift, when the thing you’re looking at is so strong but it’s actually nothing. And actually how as I’ve aged it’s become bigger. Because when I was a kid it never worried me. I’d just wander around. I never considered being on somebody else’s property. It just wasn’t a thing. I used to walk around for hours, jumping whatever fence was in my way. But then slowly you kind of get taught, you know, “you’re not supposed to do that”.

He went on to describe the abstract nature of possession as it is rendered in settler legal systems:

I mean, even being on our farm, you only own six feet of the soil. Which is really weird! I didn’t know that until – it might have been a while ago. We had this weird plane flying over with a radar on it. And it was a gold mining research plane. They were looking for gold. Where our farm is, used to be a gold mining little village. And all the local people were going hey, what’s going on here, you can’t just fly in and start to want our gold. And at the town meeting, they said six feet down, it doesn’t belong to anybody.

Cross is referring to the ambiguity of Crown land grants issued after 1891. Before this time, settler law is said to have adhered to the thirteenth-century Latin principle ‘cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad infernos’, which translates to: ‘whoever’s is the soil, it is theirs all the way to Heaven and all the way to the depths below’. Revisions to the Crown Land Act in the late nineteenth century placed limitations on how far beneath the surface property rights extended. The language of these reforms and the precise depth of ownership is vague. The language is far less ambiguous when it comes to resources found in the earth, with Commonwealth land grants reserving the rights to all minerals to the Crown. The precedent for this in found in a case from 1568 – the Case of Mines – which established that ‘all mines of gold and silver—the “royal minerals”—belonged to the Crown with the power to enter, dig and remove them’. Practically speaking, the states can grant exploratory and/or mining licenses to companies without the approval of the owner(s). This legal precedent forms the basis of the Queensland government’s recent extinguishment of native title over 1,385 hectares of Wangan and Jagalingou country by granting Adani Mining an exclusive possession freehold title over large areas of Wangan and Jagalingou land, including over ceremonial grounds, in order to develop the Carmichael coal mine. The ad hoc and ambiguous nature of settler law has created a situation where, as Wangan and Jagalingou Council leader Adrian Burragubba states, ‘We have been made trespassers on our own country’.

We asked Cross about his use of unconventional materials that index industrial and agricultural practices and processes: raw cotton, Round Up, raw canvas, fish hooks, found photographs, and so on. ‘I like things that are real’, he said. This preference for real objects reflects Cross’s sense that objects themselves contain certain narratives and histories and that these are often more interesting than objects produced purely by the hand of the artist:

I like the ways that you can complicate things. Like the Australian wool that I used – that itself has this long history of production, long history of Australian colonialism. I’ve sheared sheep myself, and I just think it’s a way that you can make an art work more interesting. I don’t know, it’s as simple as that. You can print it on paper, do this, that or the other, but if you just think a little bit broader around the ways that you can present things or do things, they can just become more interesting.

But Cross’s use of materials is anything but simple. The use of industrial agricultural materials in his installation for Infrastructural Inequalities gestures to the continuity between earlier infrastructural projects (captured in the archival images) and contemporary farming and land management practices. When looking at his work, one senses the agency of these materials and the roles they have played in making the Australian landscape ‘productive’ in settler terms. The images and objects form an assemblage that are bigger than their individual parts – the materials and symbols work together in a series of subtle gestures that point to massive, shared histories. In addition, we might think of this use of materials as an act of appropriation that seeks to question the logic of private property:

I like to use found things and also stolen things, I guess you’d say. Because you know, who owns stuff is quite interesting. And you know I don’t really believe in copyright, so much! [Laughs]

Later, when reflecting on a research project that took him to Te Papa Tongarewa (the National Museum of New Zealand/Aotearoa in Wellington), Cross described the odd experience of coming up against copyright laws in relation to images of archived objects:

In New Zealand I was looking through a lot of the archive stuff there and there were these shields from Far North Queensland that had no information on them whatsoever, that were just deep in the archive, nobody knows who bought them there, how they got there, anything about them, except the image of the object is copyrighted. [. . .] But it’s the copyright of the image, not of the object. Because the object, again, it took them days to find [the shields] when I asked to see them. They couldn’t even find them. But the image was right there. So that was through Te Papa, and then I was going through the National Archives in Wellington and you can sign up to get ten free images. [Laughs] But anything beyond that you pay for. And you think, what’s the point of that? Who does that serve? Surely they’re not making so much money off of people buying licences for those few photos, that it’s worth holding onto them. . . What’s the point of holding onto things so tightly and keeping them from communities?

Cross’s work often uses text – found or composed – and his titles often engage with word play. We asked him about language and its role in his work: ‘I think [text] is just another tool that you have as an artist. I think coming from a lost language as well, or knowing that English is a colonial language, which is also quite practical – I don’t know, I just like fun word games.’ This interplay between that which is present, available, and visible and that which is absent, lost, and invisible recurs as a theme in his work and thought. Wordplay points to the mutability of language and the possibilities of meaning-making. Cross attributed his interest in the word, turning on itself in a pun or double-meaning, to his background in dance and theatre. There, he says, ‘one word can so significantly change a sentence’. The drama and possibility of language is in its ability to transform – to suddenly swerve.

On the specificity of terms: we asked Cross what decolonisation means to him. He was ambivalent.

I actually think that decolonisation has become a meaningless word. I think it’s become a word that’s been adopted as a fashionable kind of marker that actually has no substance. Maybe what I mean is that it’s just the wrong question, or the wrong thing to be thinking about. Because to me it’s still a progressive line – like colonial to decolonial. And I don’t think that’s the right way to think about it. . . . If I had to commit to some sort of decolonial thinking, or statement about what it is, it’s an internal space of, like, letting go of the baggage. . . I don’t know, I think, decolonial, it’s more like, decapital. Colonialism’s not the issue, capitalism is the issue. Without capitalism you wouldn’t have colonialism in the first place.

To think of ‘decapitalisation’ rather than decolonisation, as Cross suggested, is to understand colonisation in its larger, longer history as a project of expansion, extraction, expropriation, and accumulation. In this sense, it points to possibilities for fighting and making new futures. Australia will never be decolonial if it remains a capitalist economy. The history of capitalism is also the history of white supremacy. Capitalism is always racial capitalism.