Eve Vincent

November 2019

Craig received a letter. He told me he found it ‘very blasé’. He was trying to get off the Cashless Debit Card shortly after an official trial of the card commenced. This letter was from a Department of Human Services ‘official’, to use Max Weber’s (2006) term, whose loyalty lies to an office ‘devoted to impersonal and functional purposes’ (51).

Craig received an impersonal letter – a bureaucratic response – explaining the rules. It basically read, he says, ‘suck it up, piss off’. He memorised this letter writer’s name.

The Cashless Debit Card (‘the card’) represents an experimental technique of welfare delivery. The card sequesters eighty per cent of a working-age social security recipient’s income support payments in three geographically bounded Australian trial sites (in a fourth trial site the card is issued to income support recipients aged thirty-five and under).

Eighty per cent of payments available on a debit card are barred from operating at any alcohol or gambling outlet across the nation; the remaining twenty per cent is deposited into the recipient’s bank account and can be withdrawn as cash.

Ceduna, a small South Australian town on the edge of the Nullabor was the first trial site. Since mid-2017 I have been spending time with people affected by the card’s introduction, such as ‘Craig’. Pseudonyms are used here.

Around seventy-five per cent of the almost 900 people on the Cashless Debit Card in the Ceduna region are Aboriginal; around twenty-five per cent living in this trial site are Aboriginal.

But the card, introduced in 2016, is apparently race-less, impersonal, not narrowly targeted. Issued to ‘the biggest mob’, as one person expressed it, the card is silver-grey, and looks just like a Visa debit card. Former Minister for Human Services Alan Tudge carefully explains that the card was introduced in select areas in response to high levels of alcohol-fuelled violence, and that this ‘is not an [I]ndigenous issue – it is a welfare issue’ (original emphasis).

Dustin, an Aboriginal critic of the card, explains it even more carefully. In Ceduna, he believes, the card is effectively addressed to a core group of Aboriginal problem drinkers. But to explicitly target those people, see, ‘that there, that would be direct discrimination.’ So, ‘they pulled the blanket over everyone’. Even whitefellas! Rose is a whitefella and she reckons, ‘If anybody sort of says anything . . . “Oh, well, we didn’t want to be racist.”’ Dustin concludes, ‘This is a racial discrimination, you know, against Indigenous people.’

This isn’t direct discrimination, it’s racial discrimination, according to Dustin. His analysis is instructive. In the multicultural liberal present, laws seemingly protect against ‘direct discrimination’. One option is to suspend those laws, through declaration of extraordinary circumstances, and urgent need. For example, the Cashless Debit Card’s precursor, the BasicsCard, was introduced as part of the Northern Territory National Emergency Response (the ‘Intervention’). The Intervention saw a suite of legislation passed after the suspension of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975. But the Act has been reinstated; to suspend it again would draw attention to the place of race. Instead, the word welfare is even italicised. It’s not just that the problem needs to be spoken about differently, it must also be seen differently. In a disciplinarian voice, the state says the problem is behaviour. It sees people being irresponsible. In its caring guise, it says the problem is the harm caused by addictions, the effects of which ripple out to hurt and deprive not just the addicted but their kin, their community, the whole town. It sees vulnerability. The card promises to protect people from the destruction wreaked by others, and from self-destruction.

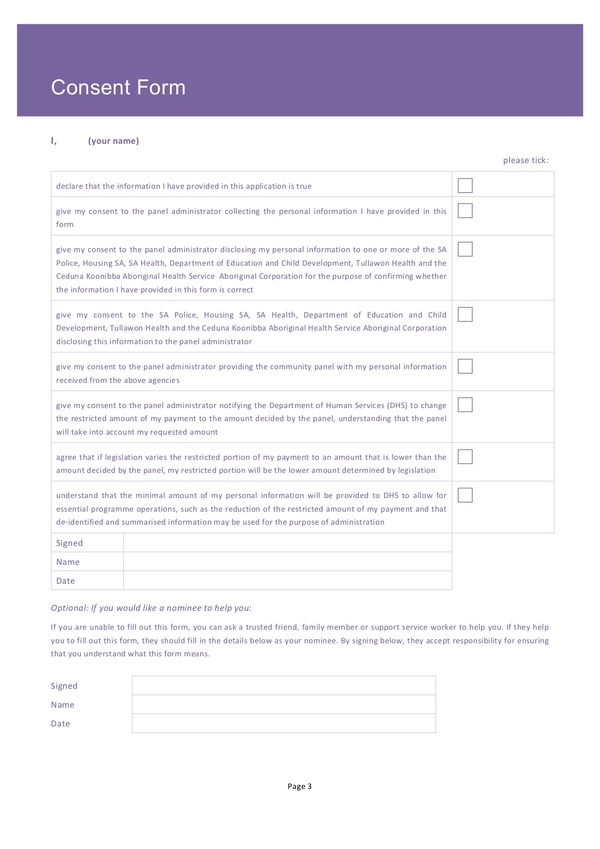

The card applies then to categories of income support payment recipients, not certain identity categories, and the same conditions are applied to all. At least at first. It is possible to alter that eighty-twenty split of monies. The first step involves some paperwork.

‘Paperwork is boring’, writes anthropologist David Graeber (2012, 108). And yet, ‘in most existing societies at this point, it is precisely paperwork, rather than any other forms of ritual, that is socially efficacious’.

Filling out this paperwork is potentially socially efficacious if severely constrained: card holders are entitled to apply to a ‘Community Panel’ to explain why instead of having eighty per cent of their monies quarantined onto the card, this amount should be reduced to fifty per cent, with up to fifty per cent entrusted into the applicants’ bank account, and hence available as cash. (In mid-2019 a further process was introduced, which provides a mechanism for card holders to apply to exit the trial completely. At the time of writing, this has yet to be implemented).

A set of guidelines outlines ‘the legal parameters, the decision making process, the values and the code of conduct’ of the Community Panel overseeing the first process. Formality and fairness characterise this anodyne document, which explains that panel members adhere to the published guidelines in order to make ‘decisions that support a safe and positive community’.

Have you applied to the Community Panel? I ask Uncle Bert. ‘No.’ Do, you know about it? ‘No.’ Have you applied to the Panel? I ask Elisabeth. ‘Um, I don’t know how to go about that at the moment.’ I talk to Maude, the central figure in a large Pitjantjatjara household that breathes in, filling up and expanding, then exhales, releasing, shrinking. The Panel? ‘No, we didn’t know about that! Them things, we need to know. . . . Thank you for bringing that up, Eve.’

For anthropologist Tess Lea (2014), the policy design cycle produces a ‘surfeit of documents that are designed not to be read’, so dense that ‘they actively repel close attention’. The ‘eye-glazing, unfriendly documentary hulk’ of tenancy agreements results in paperwork that is not read by the people putatively addressed by the document as its readers. But this application form, as well as the paperwork about this paperwork, is plain-speaking and readable. And if you can’t read, press here and it will be read aloud. Too fast in parts, rushing through yes-slash-no, but a deep male e-voice designed to soothe and calm.

And still the application process and its effects makes starkly clear the racial, biopolitical, and interventionist dimensions of the Cashless Debit Card trial.

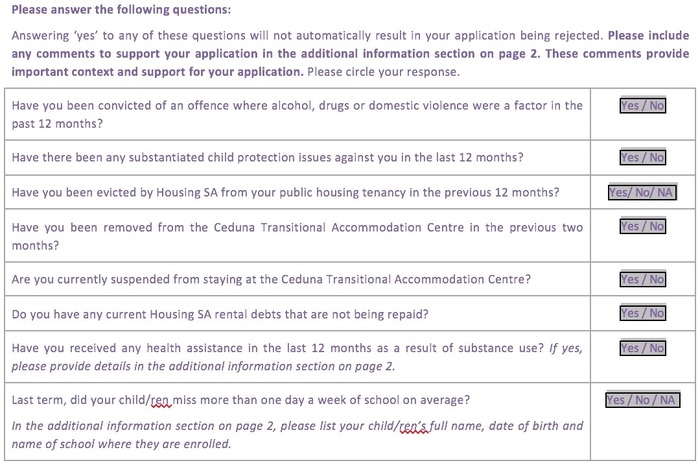

Have you received any health assistance in the last twelve months as a result of substance use? Last term, did your child/ren miss more than one day a week of school on average? Have there been any substantiated child protection issues against you in the last twelve months?

And: Have you been removed from the Ceduna Transitional Accommodation Centre in the previous two months?

Transitional accommodation. That’s better known as ‘Town Camp’, the hammered-flat dusty bowl where pink salt bush sprouts beneath the railway line. That’s where remote-living ‘countrymen’ come to stay.

Town Camp is administered by Fields Security Group, whose accommodation workers attend to people’s needs and enforce Town Camp rules. A locally circulated job advertisement calls for ‘customer service’ experience, and Fields Security Group’s website talks of personnel providing ‘a visible security presence’ and ‘demonstrating a broad range of skills from general guarding to highly specialised security roles’. (Just another day in the Kyriarchal system, Behrouz Boochani [2018] might conclude?)

‘Papa Wiya’, reads the Town Camp entry sign. No dogs. Rules in Pitjantjatjara; addressed in Pitjantjatjara.

So when Rose, the whitefella introduced above, went to apply to

The panel. The so-called panel that was actually, um, to access this panel, you had to pass a little survey. . . . It was about, yes and no, about have you been kicked out of Town Camp? Are you barred from the pub? If you’ve got a domestic violence order, that kind of shit. Yeah, pardon.

What kind of ‘shit’ is this? Is it white people also being treated like shit? Or perhaps it’s all that talking shit about the race-less trial?

It can be offensive to be treated impersonally. Craig refers again by name to the person who wrote that blasé letter. He kindly suggests they need something ‘remedial’. A lesson in ‘how to deal with people in a better manner’. Aero thought about applying to the community panel. But ‘they don’t know me from a bar of soap!’ Kieran received an automated robodebt. And he received another Centrelink letter, with a woman’s signature, a manager’s name. He called to speak to her and discovered that those letters bearing her name don’t ‘even go past her!’ ‘They don’t go via her!’

Where now to direct his fury? (At me, it turns out, momentarily). The authoring of an un-authored generic document was an injustice that followed the injustice of robodebt, a well publicised scandal that asks income support recipients to become archivists and ideal bureaucracies, keeping records of working rhythms flattened by algorithms.

And then there’s Helen’s story. She was on ‘eighty-twenty. Eighty per cent on the card and twenty per cent in my bank account’. And someone said to her, ‘You should go for the fifty-fifty.’ She submitted her application:

There’s a job network place. Behind the bakery in the mall, yeah, in there. It’s not their fault, the girls there are wonderful. Any time I’ve been in there they’ve been just great and they’ve got the [Cashless Debit Card helpline] number. They just dial it. They don’t even have to look it up anymore, so that’s how often they have to ring it. I had to take it in there, and they looked it through, and they said, “Oh, you won’t have any problems at all. Look at this.” Rah-rah-rah. Then I waited three months before I got a letter, in a secondhand envelope, that had stuff stuck over the previous . . . What it had been used for. It said, “You won’t be getting your fifty-fifty, but we’ll give you sixty-forty.”

Those ‘girls’, they are immediately available, affirming, familiar. The distant panel moves slowly. The envelope is secondhand. A good recycling initiative maybe, but it compounds Helen’s sense of injurious and impersonal treatment.

It can be offensive to be treated this personally. Samuel rang up about the panel but his close kin, who was connected with the panel, reasoned with him. Why did he need more access to cash when he had so many automatic bill payments set up? I mention to Cheryl that I am interested in the card and she yells and yells and yells something about a cousin of hers sitting in an office deciding if she’s been good.

Rose didn’t go ahead with the application in the end. ‘I don’t need that kind of scrutiny.’

Dustin – jangling, jumpy – explains again: ‘There’s a lot of people that won’t go because there’s personal problems. They do not have to tell a panel why they are stressed out! That is not the panel’s or the government’s business!’

According to a Freedom of Information request I lodged in September 2018, the Ceduna Community Panel had approved 140 applications as of 31 August 2018:

- eight applicants have had their restricted amount reduced to fifty per cent;

- eighty applicants have had their restricted amount reduced to sixty per cent;

- fifty-two applicants have had their restricted amount reduced to seventy per cent.

Helen received that letter. ‘You won’t be getting your fifty-fifty, but we’ll give you sixty-forty.’ While some rules and procedures are available and explained in triplicate – a PDF version, a word version, the soothing e-Voice version – with Frequently Asked Questions to supplement, the deliberations of the Community Panel remain opaque.

Helen sums up: ‘And to me, that’s just a power trip.’

Craig is white and propertied. He understands this to be part of the reason he eventually secured an exemption to the trial, under another process again. Separate to the Community Panel process, a little-known Wellbeing Exemptions clause states that someone might be exempted from the trial ‘if participation in it would seriously risk that person’s mental, physical or emotional wellbeing’.

According to the same Freedom of Information request, as of 31 August 2018, a total of twenty-eight people had been exempted from the Ceduna trial. Of these, five were identified as Indigenous and twenty-three were non-Indigenous or not identified as Indigenous.

Helen shows me the card she was originally issue in March 2016, when the trial first began, pointing out its 2019 expiry date. She had her suspicions all along that the one-year ‘trial’ would never end. Others share cards, lose cards, are issued temporary cards, and sent new cards. According to federal government data, the total number of cards issued to people in the Ceduna ‘trial site’ stood at 4,487 by the end of 2018.

And apparently, when some people were first issued the card, they got out their scissors and snipped it into little pieces.

Cutting up the card; cutting up transcripts to get at cut up lives. I’ve pursued a slightly jagged style in this essay in a hope to bring the reader closer to the pent-up suspicion, frustration, and cynicism this paperwork and these processes engender for many of my interviewees.

I’m influenced by Smadar Lavie (2012), who used multiple narrative modes, including diary entries, to capture what she sometimes describes as ‘bureaucratic torture’ (779). Lavie sketches scenarios in which agency was impossible as she sought to access state assistance as a Mizrahi single mother, in the process declaring the dispassionate analytical academic journal article formulae inadequate to the task of conveying the affective-somatic dimensions of her bureaucratic entanglements.

I wouldn’t use the word ‘torture’. I might use words like: poverty, got nothing this week, intimacy, close to me, bashing, Eddie Betts, aunties, uncles, jokes, rage, stories, nephews, nieces, diabetes, fights, pride, artefact making, speeches, false teeth, desert rock, racism, grog/gubby, elder abuse, fines, gaming. Going to Las Vegas (the pokies), gone to Port Augusta prison. God, pre-paid phones. Chronic pain, psychic pain, bureaucratic pain.

Works Cited

Boochani, Behrouz. 2018. No Friend but the Mountain. Sydney: Picador.

Graeber, David. 2012. ‘Dead Zones of the Imagination: On Violence, Bureaucracy and Interpretive Labour.’ HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 2 (2): 105—128.

Lea, Tess. 2014. ‘“From Little Things, Big Things Grow”: The Unfurling of Wild Policy.’ E-flux, (58).

Lavie, Smadar. 2012. ‘Writing Against Identity Politics: An Essay on Gender, Race, and Bureaucratic pain.’ American Ethnologist, 39 (4): 779—803.

Weber, Max. 2006. ‘Bureaucracy.’ In A. Sharma and A. Gupta (eds) The Anthropology of the State, 49—70. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.