Nina Serova

November 2019

‘this was an environment built, not for man, but for man’s absence.’

– JG Ballard

In his sci-fi novel High-Rise (1975), J.G. Ballard describes how a megalithic skyscraper descends into chaos. Like the modernist creations of Le Corbusier, the titular building is a ‘city in the sky’, complete with luxury apartments, a school, and sculpture garden. Gradually, frantic parties and innocuous squabbling over pool use between tenants from the lower and upper floors escalate into a state of cloistered mass hysteria, where residents eat their pets and live in darkness amidst their own waste.

This novel is less a metaphor for upstairs/downstairs class warfare – the residents are middle-class – than it is an observation on the building’s active involvement in the social world of its inhabitants. As relationships break down and tribes form, graffiti and vandalism appear as signs of collective degradation and failed respect for the norms of home ownership. The architect of the high-rise notes that for all their purported propriety, the residents ignore the building’s failing infrastructure in place of turning on one another.

High-Rise cautions against the fusion of basic human needs like housing and infrastructure with consumer capitalism. This blending is contested in contemporary large-scale urban developments, including the project to rebuild the Waterloo public housing estate in Sydney, Australia. Here I will focus on one aspect of this redevelopment: the community consultation surrounding the area’s rezoning, drawing on my experience as an independent community worker charged with supporting resident participation in the planning of the estate. Whether by intent, process, or circumstance, the community consultation has prescribed a singular version of reality for the neighbourhood, while maintaining an illusion of choice.[fn]In NSW, ‘social’, as opposed to public or government-run housing, is increasingly administered by non-government Community Housing Providers (CHP). Rent in a social housing property is calculated at around twenty-five per cent of income. Affordable housing, also run by non-government providers, costs about seventy-five per cent of the market rate.[/fn]

The Waterloo planning process implies the inevitability of the future of inner Sydney housing as underpinned by corporate finance and with individualised cosmopolitanism as the social norm. By prioritising urban design mechanisms and neglecting human services, it suggests technocratic solutions to systemic problems, both social and infrastructural. It also reinforces Australia’s ongoing settler-colonial project by obstructing Aboriginal residents’ ability to remain in a place that has provided cultural safety and political consciousness for generations. The implications of this redevelopment are serious: it will weaken the health of many already vulnerable people and reduce housing affordability, further entrenching social inequality. In what follows, I describe the ideological reframing of public housing in the state of New South Wales (NSW) and suggest that the process of public participation in this major state building project is essentially gestural, involving creative reasoning and a sequence of bureaucratic arrangements. The account I provide is a dominant, but not comprehensive, community perspective based on my experience as a frontline worker. From this perspective, I am unable to account for the context within which politicians and bureaucrats operate. The fact that this part of the decision-making is obfuscated is precisely why affecting change is so difficult for communities – their view is always partial.

Public Housing without Public Funds

Waterloo Estate sits on Gadigal land, about three kilometres from the city centre. It contains around 2,000 homes, the highest number in the state. Sixty-seven per cent of residents are elderly, around half are migrants, and many have lived in Waterloo for decades. The area has a high index of socio-economic disadvantage and is distinguished by a diverse and uniquely connected community. The current plan is the NSW Government’s third attempt at the estate’s redevelopment and, despite election promises otherwise, rebuilding has always enjoyed bi-partisan support. The latest announcement, predicated on the introduction of a new metro station, landed in residents’ mailboxes just before Christmas 2015.

The letter from the Minister for Social Housing began with this tone-deaf declaration: ‘The ageing Waterloo social housing estate will be redeveloped into a world-class vibrant community with more social, affordable and private housing.’ Three years passed and some details of the redevelopment plan have been made public. Especially contentious is the proposal to almost triple the area’s density and raise a handful of forty-storey towers. Working under a state-wide policy for upgrading and replacing public housing, the redevelopment will introduce privately-owned housing into the area, tripling its population. Up to sixty-five per cent of the homes will be purchased or rented privately and thirty-five per cent will be social and affordable.[fn]I use the term ‘community’ to refer to a diverse group of Aboriginal and non-Indigenous people living on Waterloo Estate, rather than to infer a singular conception of ‘community as unity’ (Peters-Little 2000, 13).[/fn]

The policy for upgrading public housing is based on no direct government funding, so NSW Land and Housing Corporation (LAHC) will sell land to pay for the project. Many residents, as well as housing advocates, are critical of the proposed social mix and would prefer increases in social and affordable accommodation to relieve a growing waiting list of people experiencing housing stress and homelessness. In contrast, the self-finance model is a solution to government’s ongoing underinvestment in public housing – the NSW government has been selling 2.5 dwellings a day for over a decade to cover the costs of maintaining the buildings.

The once-thriving post-war public housing sector was ideologically refashioned from being seen by politicians as an answer to inadequate housing to being a problem in itself. This aligned with a shift from prioritising working families to accommodating people with complex housing needs, including people who have substance dependencies, mental health problems, or are exiting carceral institutions. Today, bureaucrats adopt an economic logic, or that ‘public housing estate renewal needs to pay for itself’, as the foundation for the proposed private-social housing mix at Waterloo. Yet, when announcing the plan on the evening news, like their predecessor, the Minister for Social Housing stated that a socially mixed community would allow children to grow up with examples of ‘normal life’. The implication is that Waterloo’s poverty can be solved with new buildings that dilute its current population, and that a proximity to high-income lifestyles will have a morally elevating effect.

While the community finds the proposed social mix both patronising and promising – a resolution for the problems of noisy late-night drinkers and drug dealing – what is interesting is this slippage between social and economic rationales. The former suggests that the standard for residents is to be homeowners, and the latter submits that access to housing without personal capital is a luxury, and hence non-government financing is necessary. Both explanations frame housing as inextricably linked to markets, as real estate rather than homes, and the social relations this engenders, of winners and losers in property ownership, as the natural order of things.

Democracy with Non-negotiables

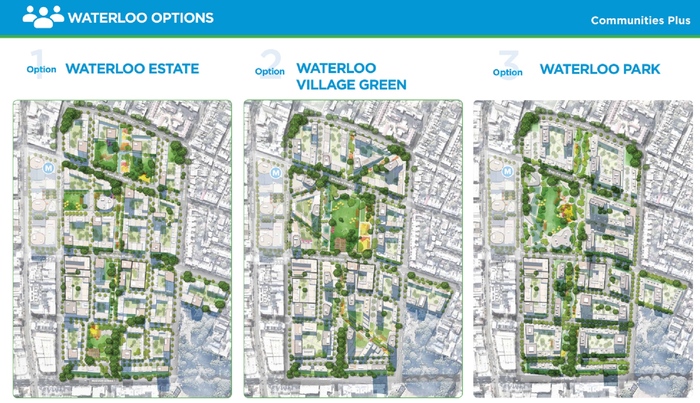

To prepare the redevelopment plan, LAHC asked people to propose their vision for the future of the area and then choose between three design options, represented in graphic obscurity (see below).

Although there is no singular resident view on the redevelopment, such opinions are typically at odds with the government’s vision. At a public meeting announcing the overview of the plan, the project’s architects faced a hostile audience. The architects’ attempt to marry the plan to community feedback in their design (in short, ‘you asked for multiple green spaces and we’ve drawn up two parks’) swiftly gave way to an admission that the unpopular inclusions are a consequence of the project’s need to self-fund: the high percentage of private housing is mandatory.

James C. Scott (1998) writes that governments tend to govern through abstractions, such as statistics, reports, records, and social categories, more than the things they represent. This is evident in the exuberant platitudes contained in community consultation reports, including aims to ‘strengthen the diversity, inclusiveness and community spirit of Waterloo’, and ‘recognise and celebrate Aboriginal culture and heritage’. Ironically, these are qualities Waterloo already has, but will likely lose in this redevelopment. Around ten per cent of the suburb’s residents are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Waterloo is adjacent to Redfern, which is widely recognised for its cultural and political significance. Containing the Block, a patch of urban land returned by the Commonwealth to Aboriginal ownership (NSW Legislative Council 2004, 36), it is the product of Indigenous self-determination. Also, many residents, including non-English speakers and those who are socially isolated, rely intimately on their neighbours for social contact and basics like groceries. Without a deliberate government mandate, members of these groups will be unable to afford to live in the area. The Waterloo redevelopment is thus what Melissa Fernández Arrigoitia (2014) describes as an ‘enabler of social displacement’ (168).

Wearing Down

Between PowerPoint presentations and free barbeques, interviewers enquired about how tenants want to live alongside private residents, or what they imagine to be Waterloo’s ‘character’.

However, casual conversations with residents reveal more pragmatic concerns: When and where will I have to move? How long do I have to wait to get a leaking tap fixed? People are discouraged from making bureaucratic requests by past experiences and the commonly held perception of the housing authority as offering poor service and lacking accountability. Reports of repair needs are said to be met by surly frontline staff and lost in the system. Residents like to talk about how this feels like shouting into a void. As Fernández Arrigoitia (2014) writes about decaying lifts in a Puerto Rican housing project, or Tess Lea and Paul Pholeros (2010) argue about Indigenous housing, the deterioration of infrastructure provides an important reference point of injustice for residents, and for authorities, evidence of tenants’ lack of householder pride and culpability for disrepair.

People are fatigued by surveys, interviews, and announcements of various strategic plans. This is especially so given the redevelopment’s timeline is a protracted twenty-plus years. The initial announcement spurred tenant activism, including a tent embassy, a participatory design process, and a review of the government’s consultation, among other work. But it is difficult to maintain steam years on.

The final impediment to genuine participation is the heftiness of the redevelopment plan. It is conceptually and literally dense. In printed form, the plan would fill multiple folders with its detailed technical studies that lay out the project’s impacts on a long list of issues, from transport to shadowing. The language is highly specialised and together with the sheer volume of information, difficult and tedious to decipher. The plan is an object with a life of its own, looming over the people supposedly acting on it. Not only is it a deterrent for lay people’s involvement, it is also a source of ongoing work for various bureaucrats in charge of the plan’s drafting, finessing, and approval.

Capitalist Realism’s Built Form

Like Ballard’s story, Waterloo’s housing development shows that the prioritisation of private financial interests over resident stability should come as no surprise. But I want to point to the way in which redevelopment planning asks us to believe the socially and politically constructed myth that housing must be property. While broad-brush dismissal of all bureaucratic processes is tempting, what is more revealing is the way in which their ends are achieved, both through the deterioration of apartment blocks via neglectful maintenance and the dwindling of residents’ spirits by committee. Understanding this is a difficult task, given that the ideational and material dimensions of planning and community consultation may not always be aligned: to what extent is the plan influenced by the political will of those in power, or the way the residents were asked questions and how these were recorded, or material realities such as the repair costs of particular buildings? (see Hull 2012).

On the flipside of presumptions of government mismanagement lies the trap of conceiving all residents as formulaic victims, who, if it wasn’t for state power, would stand in active opposition. This is not only untrue but may end up misrepresenting people as casualties of an ideological battleground. A year following the plan’s announcement, most residents are indifferent to redevelopment business, or lack the time and resources to engage, except a handful of enthusiastic people who continue to front up to regular meetings. To say those individuals are solely motivated by a desire for democratic participation would be superficial. Some attend to air grievances about a prominent neighbour. Others enjoy the opportunity to speak to an audience, often announcing a new volunteering venture. Others are community meeting veterans, having cut their teeth over decades of labour action, so public organising is a familiar and enlivening activity.

In Waterloo, the challenge of maintaining unified community action over time is not limited to obstructive government policy and processes: it is possible that not all residents are necessarily interested or empowered to protest. Limited socio-economic capital, which provides resources such as spare time and specialised literacies, stands in the way of single-minded and sustained political action. Then there are personal factors. Not every resident is endowed with the sense of entitlement useful to making demands to government. As one ninety-year-old Jewish resident from the Soviet Union said to me: ‘I lost most of my family in the war. I came here when I was older and did not work for Australian society – and still I have a place to live. I thank the government for everything it has done for me.’ Whether we call it community consultation (as it is termed by government), public participation (as advocated by community workers), or aspire to the standard of community-led co-creation (embracing more recent terminology), resident involvement in the future of Waterloo faces complex obstacles. Social forces, such as century-long policy consequences, material and quotidian ones, like drawn out committees under fluorescent lights, and as always, personal investments, all shape the grinding process of community presence in large-scale urban change.

Nina Serova writes from her experience as an independent community worker in Waterloo. This essay is based on her observations of Waterloo in 2019 and views are her own.

Works Cited

Fernández Arrigoitia, Melissa. 2014, ‘UnMaking public housing towers: the role of lifts and stairs in the demolition of a Puerto Rican project.’ Home Cultures, 11 (2): 167—196

Hull, Matthew. 2012, Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Lea, Tess and Pholeros, Paul. 2009. ‘This is Not a Pipe: The Treacheries of Indigenous Housing.’ Public Culture, 22 (10): 187—209

NSW Legislative Council. 2004. Inquiry into issues relating to Redfern/Waterloo. Report 32, August.

Peters-Little, Frances. 2000. ‘The Community Game: Aboriginal Self-Definition at the Local Level.’Research Discussion Paper no. 10, 1—20. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Scott, James C. 1998, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.