Liam Grealy and Kirsty Howey

November 2019

Across Australia’s Northern Territory (NT), remote Indigenous communities are experiencing failures in drinking water supply and quality with troubling frequency. On 19 April 2018, the NT Department of Health issued precautionary drinking water advice to Garawa 1 and Garawa 2, two of the four Indigenous ‘town camps’ in the remote township of Borroloola. Routine testing had revealed elevated lead and manganese in the water supply above safe levels. Residents were told not to drink, cook, or brush their teeth with the water, while assured that the contamination was a short-term problem. The issue proved persistent, however, with the precautionary advice for Garawa 1 remaining in place until 15 June 2018. Although never publicly confirmed, brass fittings in the decades-old reticulated piping were thought responsible, with the acute problem resolved by a combination of water flushing and spot replacement of pipe and pipe fittings. Using this incident as a case study, this essay considers the infrastructure through which drinking water is provided in the NT as an object of legal and practical governance. Specifically, the survey is examined as a technology of settler-colonial governance which continues to produce forms of state intervention and care along racial lines.

Surveys and Frontiers

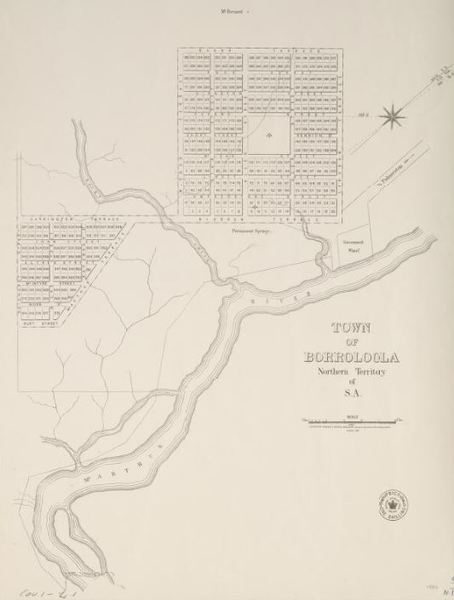

Borroloola is a very remote town in the Gulf region of the NT. It has a population of about 900 people, seventy-five per cent of whom are Indigenous, including Yanyuwa, Garawa, Mara, and Gurdanji people. Borroloola was gazetted as a township in 1885, as a rest stop for drovers on the Gulf stock route between Queensland and northern Australia, and as a service hub for surrounding pastoral stations. Tony Roberts details how the expropriation of Gulf Country beyond colonial frontiers, carved up into vast pastoral stations mostly owned by wealthy investors from the eastern colonies, depended on the widespread, state-sanctioned murder of Aboriginal people – at least one sixth of the Gulf Country population from 1881 to 1910. In the 1950s, mining surveys in the region discovered the ‘Here’s Your Chance’ lead-zinc-silver deposit, which determined the area’s ongoing significance to extractive industries, principally the McArthur River Mine established in the early 1990s.

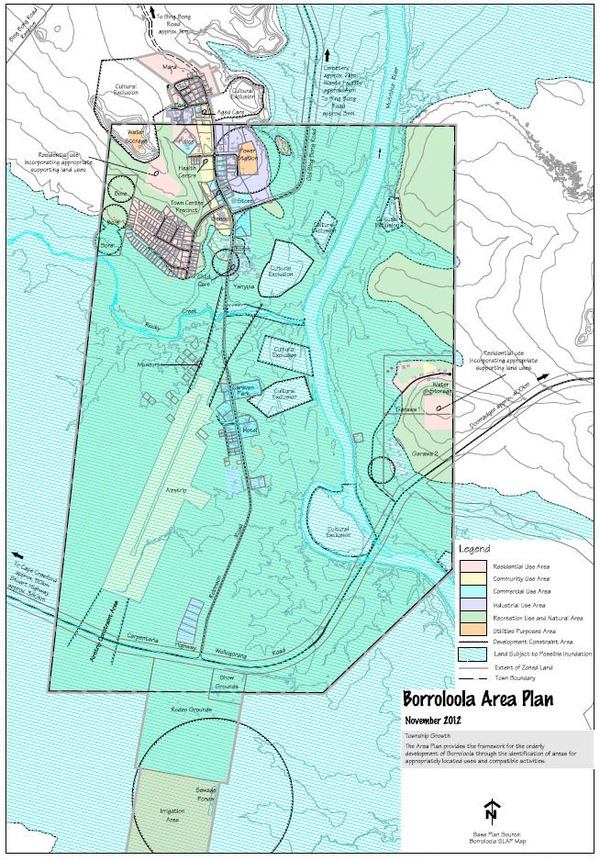

Today, Borroloola includes four areas designated in NT bureaucratic-parlance as ‘town camps’, a term which describes housing areas for Indigenous residents usually located on town peripheries (otherwise known as community living areas, and ordinarily distinguished from remote Indigenous communities, which are generally located on officially recognised Aboriginal land). As Figure 2 shows – and with implications for water provision and governance outlined below – Yanyula, Garawa 1, and Garawa 2 camps are located within Borroloola’s township boundary, while Mara camp is to the north. The McArthur River courses through the township towards the Gulf of Carpentaria, with Garawa 1 and 2 camps to the east, and Yanyula camp to the west.

As a gazetted town, which is to say, as proclaimed non-Indigenous space, Borroloola was excluded from claim with the advent of statutory land rights in the NT under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (ALRA). This differs from nearly all other pre-land rights NT Indigenous communities and outstations, which were located on either Aboriginal reserves or vacant crown land and therefore available for claim and/or transfer to Aboriginal freehold ownership under the ALRA. Borroloola township is now surrounded by Aboriginal land successfully granted under the ALRA, including Mara Camp. In 2016, the Federal Court recognised that native title continues to exist within Borroloola where it had not been extinguished by prior government actions. Yanyula, Garawa 1, and Garawa 2 camps are located on Crown Leases in Perpetuity, which are subject to native title rights and interests.

In its colonial and post-land rights histories, then, Borroloola was a stock route town converted to a mining town which is now also a part-Indigenous owned town. Perhaps unexpectedly, this is consequential for how drinking water is governed in the NT. Borroloola, as one of eighteen gazetted towns in the NT, is a water supply licence area under the Water Supply and Sewerage Supply Act (WSSS Act). Similar to other regulated water supply services across Australia, the state-owned but corporatised Power and Water Corporation (PAWC) provides its drinking water pursuant to a licence from the state utilities regulator, a customer contract, and overarching legislation including the WSSS Act and the Power and Water Corporation Act. On Aboriginal land, however, where the vast majority of Indigenous communities are located, water supply is largely unregulated. Those jurisdictions are serviced by PAWC’s private not-for-profit subsidiary, Indigenous Essential Services (IES) Pty Ltd, with no legislative mechanisms mandating licensing or particular levels of service. The strongest instrument we have found governing IES operations is an expired (at the time of writing) Memorandum of Understanding with the Department of Health which sets a regime of water quality testing and reporting in those places. We describe this variegated legal geography, following Karen Bakker (2003), as an ‘archipelago’ of water governance, and elsewhere identify a typology of six islands subject to differentiated forms of legal accountability, attention, procedure, and intervention. These are hierarchised along racial lines, and produce differentiated forms of ‘hydraulic citizenship’ (Anand 2017, 8).

The nineteenth-century act of surveying towns in the NT was crucial for producing this difference, incorporating the town from beyond the colonial ‘frontier’ into its regulated territory (Blomley 2003; Povinelli 2018). Cadastral surveys are the preeminent technology for constituting a rights-based relationship to land as property, precluding competing claims and uses over dehistoricised spaces deemed to emerge through the survey itself and the production of an ‘orthogonal grid of property boundaries’ (Byrne 2003, 173; Jackson 2017). Land subsequently reterritorialised as Aboriginal freehold ownership is now subject to differentiated, and typically less stringent, legal and monitoring regimes, by IES or private owners. Although contemporary regulatory frameworks give the impression of spatially consistent infrastructural governance across the NT, multiple regimes of property law and water governance in fact operate simultaneously and in different scales and jurisdictions.

There are also racialised differences in the governance of infrastructure at a local scale, within gazetted towns. Following the contamination event in 2018, a statement from PAWC outlined that ‘it is suspected that . . . legacy infrastructure (not belonging to Power and Water) contributed to the elevated levels of lead that were detected during routine sampling’ (Northern Territory Legislative Assembly 2018). The Garawa camps’ water supply is separate from the main Borroloola supply,1 with water drawn from a nearby bore and pumped north to an elevated tank, which drains via reticulated piping to housing. Land in Garawa 1 and Garawa 2 camps is owned under leasehold title held by two Aboriginal corporations. While these corporations exist as legal entities, they are not currently materially resourced to survey and maintain subterranean infrastructure. This means that no government agency has legal responsibility for the reticulated infrastructure that circulates water through the Garawa camps, with the landowner responsible for ‘all the plumbing from the property side of the meter’ (PAWC 2007). In Borroloola’s town camps, bulk meters used for billing are located at the boundaries of the community lease area. This means it is theoretically possible for PAWC to disavow itself of responsibility for repairs beyond those points.

Incomprehensive and Incomprehensible Surveys – The Town Camps Review

This tenure situation was noted in the Living on the Edge: Northern Territory Town Camps Review (hereafter Review), commissioned by the Department of Housing and Community Development and undertaken by Deloitte consultants at a cost of $2.37m. The Review recommended urgent upgrades in both Garawa 1 and Garawa 2, determining that the supply provided by the local bore and storage tank was ‘inadequate’, but that the rest of the network was ‘generally compliant with [PAWC] standards’ (DHCD 2017). It also proposed that the Borroloola town drinking water supply network be extended across the McArthur River to Garawa 1 and 2 ‘as a matter of urgency’ (DHCD 2017).

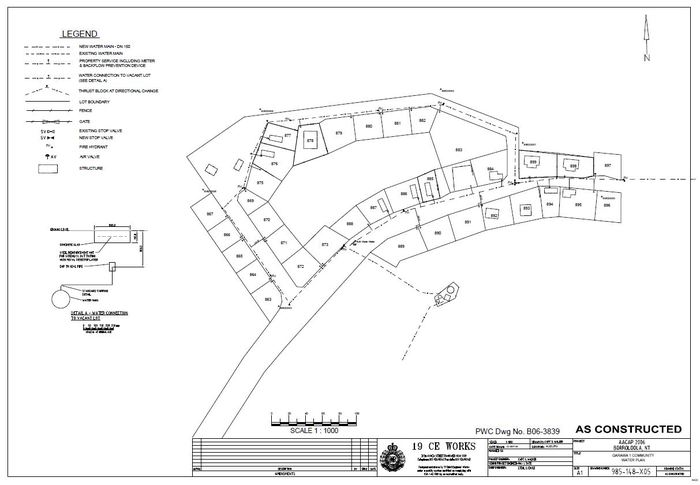

Delivered to the NT Government in August 2017 but not published until April 2018 – apparently due to its unwieldy 16,000-page length – the Review is basically an infrastructural survey of the NT’s forty-three town camps. An overview report and a summary by regions are supported by five section reports and twenty-five appendices. Moving across scales, the detail is increasingly fine-grained – summaries of findings such as ‘Water supply networks, bulk water meters and fire hydrant coverage are generally non-compliant’ are underpinned by photographs of individual water meters in specific town camps and notations specifying missing or broken handles. The incredible detail in the Review built on, and indeed was structured by, numerous prior surveys of such contexts. These surveys, such as those produced by the Australian Army’s ‘Connecting Neighbours’ Borroloola infrastructural upgrades in 2006, were included in the appendices. The mediated experience of investigating Borroloola infrastructure via the Review thus echoes the practice of its compilation, with photographic practices oriented by prior surveys.

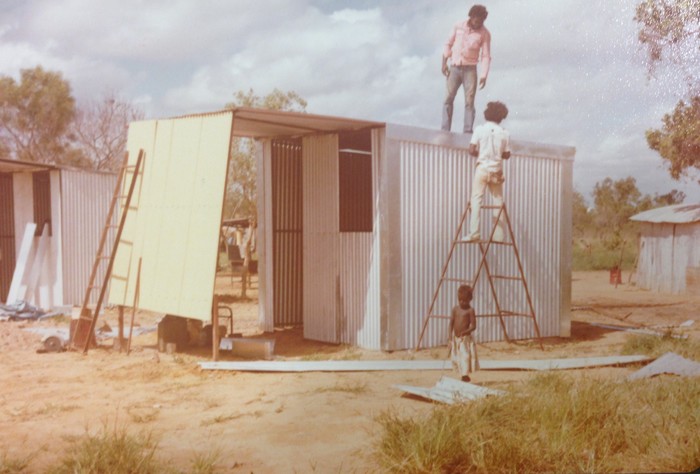

This mammoth task in surveying, documentation, and assessment is structured to some extent by the logic of the ‘secure tenure’ policy, which has underpinned state approaches to infrastructure provision in the NT since prior to the 2007 Northern Territory Emergency Response (‘The Intervention’). Indeed, one of the major effects of the Intervention was the extensive survey program it initiated. Until the early 2000s, public assets and infrastructure were constructed by NT governments on Aboriginal land and within town camps on native title land without formal property arrangements. Since 2006, an amended ALRA and the compulsory acquisition of sixty-four remote communities under the Intervention has led to the proliferation of leases on Aboriginal land as the means to secure government funding (for example, under the 2008 National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing [NPARIH]). In theory, a government department or private party secures a lease, licence, or easement for a town camp, housing precinct, or specific piece of municipal infrastructure, and thus assumes responsibility for its maintenance and repair.

In most instances, securing a lease requires knowing what’s there. For various reasons, leases have not been agreed upon at Borroloola town camps, with new housing construction significantly delayed. While the NT Government has pursued leases for bores, water towers, sewage ponds, and so on, reticulated piping in drinking water networks remains a gap in this attempt to comprehensively inscribe material infrastructure within a textual framework specifying legal responsibilities. In the late 1970s and 1980s, the federal government funded Aboriginal corporations to install drinking water and sewerage infrastructure for which there are inconsistently detailed and available records today (noting that the NT Government inherited responsibility for town camps in 2008). While it would be reasonable to assume that the Town Camps Review remedied this absence, given its extent and detail, it failed to assess subterranean reticulation in the Borroloola town camps using either potholing or excavation. Thus when PAWC responded to the drinking water contamination in 2018, it did so without a legal claim on the infrastructure or knowing exactly what lay underground.

Surveys and Guesswork

It is easy to presume that the state governs from a position of knowledge, through technologies of measurement such as the survey that make society and the environment legible. However, surveys only partially achieve this assumed legibility. The survey is more often a technology for claiming access and ownership over what exists than it is a representation of those objects. In practice, governance is far more reactive and pragmatic than planning processes and policy declarations suggest, proceeding from a limited knowledge base and by makeshift methods. When things break down, the lack of accurate documentation to mediate between the thing itself and the authorities charged with its repair is one part of the legacy of ‘legacy infrastructure’ in the NT. It is also a significant impediment to the hydraulic state, for which ‘seeing like a state means looking at records more often than the things they represent’ (Hull 2012, 166). Such documents are rarely comprehensive and, even if they once were, the inevitability that infrastructures will crack, corrode, and deteriorate puts an expiry date on their accuracy. Against these cracks, and alongside these gaps in knowledge, what remains is governing with guesswork.

Works Cited

Anand, Nikhil. 2017. Hydraulic City: Water and the Infrastructures of Citizenship in Mumbai. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bakker, Karen. 2003. ‘Archipelagos and Networks: Urbanization and Water Privatization in the South.’ The Geographical Journal, 169 (4): 328—41.

Blomley, Nicholas. 2003. ‘Law, Property, and the Geography of Violence: The Frontier, the Survey, and the Grid.’ Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93 (1): 121—141.

Byrne, Denis R. 2003. ‘Nervous Landscapes: Race and Space in Australia.’ Journal of Social Archaeology, 3 (2): 169—193.

Department of Housing and Community Development. 2017. Living on the Edge: Northern Territory Town Camps Review. May. Deloitte, Northern Territory Government.

Hull, Matthew. 2012. Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Jackson, Sue. 2017. ‘The Colonial Technologies and Practices of Australian Planning.’ In S. Jackson, L. Porter, L.C. Johnson (eds) Planning in Indigenous Australia, 72—91. New York: Routledge.

Povinelli, Elizabeth A. 2018. ‘Horizons and Frontiers, Late Liberal Territoriality, and Toxic Habitats.’ e-flux (90).

Power and Water Corporation. 2007. ‘Our Customer Contract.’

Roberts, Tony. 2009. ‘The Brutal Truth.’ The Monthly. November.

Notes

- A tender was awarded in April 2019 to NCP Contracting Pty Ltd for the ‘Garawa Water Quality Improvement Project’. ↑