Christen Cornell and Thuy Linh Nguyen

November 2019

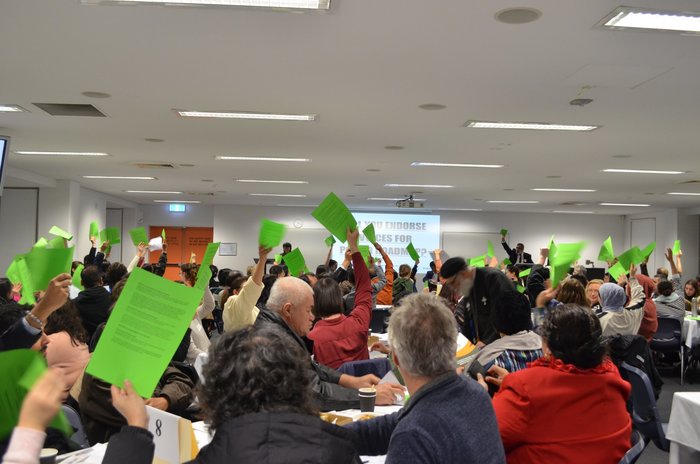

On 14 March 2019, 2,000 people from sixty civil society organisations filled Sydney Town Hall to demand the major parties in NSW take action to address the affordable housing crisis and to call for a clean, affordable energy future for all. Badged as the Town Hall Assembly (The Assembly), the meeting was the largest of its kind ever held in Australia, and situated its questions about equality and infrastructural access squarely within the context of climate change.

The Assembly was extremely diverse. It was organised by a coalition of faith organisations, community associations, and trade unions. One quarter of the gathering was from Sydney’s culturally and linguistically varied Western suburbs: 150 Sikh leaders in bright orange turbans and saris filed into the Town Hall ringing their bells; Hazara refugee women stood proudly for recognition in the roll call; a young south Indian man related his experience of floods in Kerala, and how his rental status in Sydney now locks him out of accessing subsidised renewable energy technologies such as solar panels.

The Assembly was a culmination of years of coalition-building, research, advocacy, and community organising that brought many otherwise disempowered groups and people together to confront questions of power at one strategic moment, before the NSW Election 2019. Here, power refers both to political resources and the energy required for houses to function. Because while many of these communities are rich in social, cultural, and political capacity, Australia’s energy system is set up in a way that disempowers them. This system comprises government bureaucracy, private energy companies’ commercial interests, legacy infrastructure, and more recent investments in a shift from oil-based to renewable power. An ability to navigate this system requires particular literacies in bureaucratic and technical language, the time and ability to analyse different energy programs, and sufficient economic resources to perform the self-governing work of the neoliberal citizen.

Indeed, Australia’s energy system is part of a broader neoliberal logic that privileges the interests of private markets over public infrastructure which would otherwise be accountable to the people through liberal democratic techniques of administration and participation. This neoliberal framework positions energy consumers as individuals who will act to maximise their individual interests, while ignoring the social factors that restrict access to the energy market and that make negotiating that market complex. Rendering individuals simply as energy consumers means that citizens lose power to hold the energy system accountable for the inequalities it produces.

The inability of everyday citizens to hold actors of Australia’s energy system accountable has real consequences. When configured simply as consumers, rather than as citizens with a right to a service, householders can be punished for an inability to pay their bills. Low-income households are particularly exposed to disconnections for lack of payment. They are penalised for being poor. And as climate change drives up temperatures, energy use and energy prices, already vulnerable households are at risk of sliding into further financial instability.

How then might we intervene in this association between social position and energy security? The Sydney Alliance is a community activist organisation that seeks to answer this question. Its model is to organise diverse civil society into broad-based coalitions that are committed to disrupting the established power structures underpinned by neoliberal capitalist assumptions that have disempowered people. This is termed by the Alliance as ‘relational organising’ and was encapsulated in the Town Hall Assembly event: a hall full of people from the local churches, mosques, temples, synagogues, joined by the local business council, community housing providers, tenants of social housing, trade unionists, and community service organisations, collectively calling on governments and the private sector to commit to rebates to provide affordable solar power for low-income households. Relational organising, which has been tried and tested in the United Kingdom and the United States, has demonstrated that by bringing together different civil society actors (that do not always work together), community organisers can enlist the responsibilities of elected officials over vested interests in the private sector.

In this piece, we examine the approach of the Sydney Alliance, and its reliance on the ideals of liberal democracy as a ready-made infrastructure for political change. How might the Sydney Alliance’s building of coalitions present a challenge to the private sector in the energy arena? What are its limits and possibilities? Potentially, the functioning of the Alliance model is limited to particular cultural, economic, and geographic contexts, such as urban and suburban communities, and synergies between specific cultural groups. Whether this model is capable of including remote Indigenous community interests within its coalitions, for example, is yet to be tested. However, the purpose of this article is to lay out the experiences of those working with this political paradigm, and to consider the relationship between the kind of affective power produced by coalitions, and events such as the Town Hall Assembly, and the possibility of deeper structural redirections in the country’s energy system.

‘Fine for some’: climate change and privatisation

We come to this article as parties in our own loose coalition, each working on projects related to affordable and appropriate housing, and energy, in the context of climate change. Thuy is an Organiser with the Sydney Alliance (which organised the Town Hall Assembly), who co-runs Voices for Power, a campaign which advocates for cheaper and more sustainable energy. Christen is a researcher at the University of Sydney, undertaking a project on the ways in which precarious housing can exacerbate household vulnerability to extreme weather events.

Across these projects we have seen that adapting to climate change requires coordination, negotiation, and organising. There needs to be a wholesale transition away from fossil fuel generated electricity, which would mean a significant redistribution of capital investment. In Australia, this would also mean the transition away from coal mining – an industry that has been viewed as the backbone of the national economy. The Sydney Alliance sees the State and Federal governments as the key actors in managing this difficult transition, to ensure that citizens’ as well as consumers’ interests are considered. However, while the majority of Australian people support strong climate action and have reported feeling the pressures of ever-rising electricity bills, the conservative Liberal–National Federal Government has held back from making necessary reforms. In this neoliberal framework, the Government has vacated responsibility for reforming the broken electricity market (see here and here), pushing for individuals to solve these problems.

This might be fine for those with resources to weather the effects of climate change and expensive energy. However, according to this model, those who are already the most vulnerable will suffer the greatest impacts, since they’ll be left behind in the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy production.

At the Town Hall Assembly, a single mother of four told her story. Reliant upon Centrelink payments, she was unable to keep up with climbing energy prices, and so to avoid disconnection she took the step of approaching the energy company. At no point did company representatives direct her to their hardship programs. They treated her as someone with a debt rather than someone who needed their assistance in recovering from financial hardship.

Then, after a member of her family passed away, this single mother was evicted from her home. With family and community assistance, she is now getting back on her feet; yet the debt collectors are ever-present, pursuing her for the money owed to the energy company. Energy companies and the government purport to have hardship programs and support for vulnerable ‘customers’, yet too often the marginalised are treated as miscreants, and this further entrenches the structural disadvantages that they experience navigating the energy system.

Similarly, as climate change impacts become increasingly severe, under-resourced communities in urban and regional Australia will have to weather the impacts of extreme heat and cold, and will be expected to do so on their own dime. Already, we have heard stories of pensioners who risk overheating during hot days for fear of their power bill, and of others who roam the local shopping mall to escape the heat. A Voices for Power participant reported of how she took her children to the 24/7 K-Mart so they could rest. These examples of people using commercial spaces to mitigate the effects of climate change highlight another barrier presented by privatisation: so much of what we might previously have imagined as common and communal space has become consumer-focussed, highly policed, and unfriendly to those to unable ‘buy’ their right to be there.

Residents living in low-cost housing are also more likely to receive higher energy bills, since affordable housing is often the most difficult to power, being old, poorly sited, and/or poorly designed. In Sydney, affordable suburban apartments are often characterised by inadequate ventilation, high indoor temperatures, and inflated energy bills. In the regional centre of Lismore, most affordable housing is located in the bottom of the valley, alongside the river, and is the first to be impacted by extreme wet weather – such as the flooding that decimated the town in 2017. Caravan parks – a traditional mode of cheap housing – are typically located on flood plains, since this land is least desirable for development. Recently arrived refugees are fast-tracked through the state housing system if they agree to housing in regional areas, which means older housing stock that is draughty in winter and expensive to warm.

In parts of regional and remote Australia, extended drought, the redirection of rivers for farming and mining, and increased temperatures have made Aboriginal communities ever-more dependent upon municipal energy, water, and housing infrastructures. And yet, as responsibility for these services is passed from government to private operators (or community operators now expected to bid for competitive contracts), residents of Aboriginal communities are reconfigured into consumers, whether or not there is a viable local industry in which they might take up paid work. In Walgett, NSW, for example, where the twin rivers that have long-defined the town have gone dry from drought and damming for cotton production upstream, Aboriginal communities are increasingly reliant upon commercial water and energy providers to stay alive. Insurance premiums on their community operated housing push up the rent, and market logics around the ‘viability’ of the town have some wondering whether the State will continue to support ongoing Aboriginal presence in the area. In this way, privatisation often sets the conditions for vulnerability. Those with the capacity to be ‘good consumers’ can purchase protection. They can be part of ‘the network’, whereas those without access to the market are left out in the cold – or in the heat, as things may progress. Disconnections become a punishment for those who are unable to pay their bills. They become a punishment for being poor, further exposing people to risk and social and economic isolation.

Building connections, alliances as public infrastructures

A key response to challenging this neoliberal logic that pervades our energy and economic systems is to build connections. Where rendering people as individual consumers disempowers the most socially marginalised, the building of coalitions across diverse organisations builds the power of civil society to influence politics towards a fairer system. Power is built from organised people so that vulnerable communities can develop agency to choose and create their own solutions to problems. As a community leader said about the Voices for Power Campaign, ‘there is power in unity and diversity!’

Since early 2017, the Sydney Alliance’s Voices for Power Campaign has worked to build connections across seven different migrant communities in Sydney, to take action in response to cost of living pressures caused by rising costs of energy, to increase access to renewables, and to confront climate change. This Campaign arose because it is recognised that migrant communities are often vulnerable in the energy system. Such communities are often low-income, experience language and cultural barriers, and are already experiencing other forms of isolation from mainstream Australian society such that decision-making processes ignore their particular experiences. In the last two years, the Campaign has hosted over 50 events with churches, mosques, temples, and community organisations in these culturally and linguistically diverse communities. This work is now led by the diverse leadership of a Uniting Church minister from the Tongan communities, an Imam, a Fijian-Indian woman who is Buddhist and a strong leader in the community sector, a Vietnamese community worker who organises migrant women workers around their rights at work, and a Filipino leader who founded an affordable housing cooperative. These Voices for Power leaders, together with key housing sector organisations, agreed to organise the Town Hall Assembly as a political action that sought to influence the election commitments of the major political parties around housing and energy policy ahead of the NSW and Federal election in 2019.

The power of this diverse coalition is illustrated in the following story. Ahead of the Town Hall Assembly, the major political parties had not committed to many of the Assembly’s policy demands on housing and energy. As a final response, a group comprising a union leader, the head of a peak housing body, and a Coptic priest representing the NSW Ecumenical Council met with then-Opposition Leader Michael Daley’s chief of staff in order to demonstrate how broadly the issues of affordable housing and energy affects citizens in Sydney. Further, this delegation demonstrated that these diverse organisations with broad membership are prepared to act together. Within two days of meeting with this diverse delegation, NSW Labor came to the table with two new policy commitments regarding homelessness and social housing.

On stage at the Assembly itself, these community leaders conducted a public negotiation with elected politicians about their government’s positions on energy and housing. Rather than accepting stock responses, the politicians were compelled to answer directly to their questions – something many participants had not witnessed before. In this space, participants felt they had reclaimed their civil rights to hold elected officials accountable. Building connections across these diverse communities based on their common concern had given these communities a voice to hold decision makers accountable to their constituents, and to implement solutions to address these structural inequalities.

The communities were involved in the founding of a common agenda, encompassing the political actions required to secure the political leaders’ attendance and policy commitments. In the weeks leading up to the action, they made collective decisions to accept or challenge the political leaders’ specific offers for how to work together on these issues. Then at the Assembly, they confronted the political leaders on their policy positions on stage. No longer simply consumers, or individual victims of an unfair energy system, participants became constituents for power. In this, the Alliance model suggests the possibilities for alternative political infrastructures that might be assembled by those locked out of energy access, demonstrating how otherwise perhaps conflicting communities might find shared interests, and so subvert a system that benefits from the dissolution of social and political connections.