Naama Blatman-Thomas

November 2019

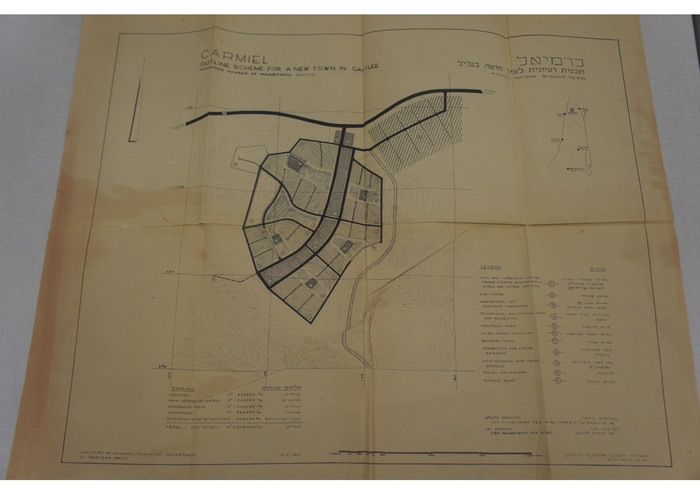

Undoing Indigenous Infrastructures

In June 1963 the construction of Karmiel – a Jewish city in Israel’s Galilee region (Fig. 1) – was well underway. By then, the Israeli Knesset (parliament) had authorised the expropriation of over 5000 dunam of land from Palestinian villagers in the western Galilee and scores of mainly Palestinian construction workers were hard at work to lay the foundations for the arrival of Jewish immigrants to the new town.[fn]A dunam is a unit of area that designates 1000 m2.[/fn] For those who lost their land and livelihood for the benefit of the Jewish settlement, these were turbulent times. In the following excerpt from the Israeli newspaper Ma’ariv, a Jewish reporter describes an impromptu encounter with two Palestinian men against the backdrop of Karmiel’s advancement (Fig. 2).

We were sitting on a grey rock in Beit HaKerem Valley and smoking cigarettes with two friends-for-a-moment, native to this valley. We were looking at the compressor stationed far from us, thundering like an upset giant and spewing black smog. The echoes of its blasts were hammering, biting at fields of rock, disseminating faraway, reverberating atop barren hills.

“Soon they are going to blast there,” said the young mustached man from the village Nahef. “We used to do a lot of rock blasting here,” said the old man from the village Bi’na — “but not with compressors. With our hands. With a metal stick. Three, four hours for one hole. With a compressor, it takes five minutes. But one compressor costs about twenty thousand liras.” […]

“We insisted for a long time on this land […], we didn’t want to sell it. My granddad didn’t sell and neither did his granddad, so why should we sell? We insisted. The Government confiscated. We went to trials. We went to the High Court in Jerusalem and we lost. They took the land and that’s it.” “They paid money,” growled [sic] the old man. […] “We didn’t want money. We wanted our lands. Why? Because the land is a part of the farmer’s soul” (Talmi, 1963).

Captured in this text is a moment of profound transformation. First and most obviously, the landscape itself was changing as heavy machinery flattened the land, eliminating many of the region’s natural resources to make room for residential expansion. Second, a new economy appeared to be emerging with the removal of manual quarrying and agricultural fields in favour of industrial extraction and new factories. These changes affected a broad range of Palestinian villagers who utilised the land for subsistence, mainly as farmers and miners (or mine owners). But of course, it is not just ‘the natural environment’ that was undergoing transformation; as a settler-colonial project, the Jewish settlement was taking form atop and beneath a dissipating Palestinian landscape, while targeting this very landscape (Leshem, 2016). Once the Indigenous inhabitants of the region, in the aftermath of this transformation, Palestinians would come to be regarded by Jewish people as immigrants or foreigners in the city.

In the face of this transformation, this paper asks what the infrastructural project of building a Jewish city in the Galilee did to the identity of the landscape and to the project of Judaisation within which Karmiel was established. The term Judaisation refers here to a suite of practices undertaken by Israel within its national plan to create an ethnic Jewish state in Palestine (Fig. 3). Such practices were aimed towards the land – turning Palestinian land into Jewish property – and its people, namely, de-populating the territory of as many of its Palestinian inhabitants and re-populating it with Jews. These practices echo Patrick Wolfe’s (2006) articulation of settler colonialism as a project of replacement and elimination, and physical infrastructure was crucial to these processes.

In material terms, the project of Judaising the Galilee included laying down water and sewage pipes and electric wires, building thousands of apartment units, single-standing houses and industrial factories, and paving new roads to afford access to the emerging town (Fig. 4). Much like colonial projects elsewhere, the logistics of infrastructural development were seminal to the effort of settling the new territory.

Infrastructural ‘Improvements’

In Karmiel, alongside practices of dislocation, dispossession and (partial) erasure, infrastructural development was used to justify the Judaisation project itself. Rebuffing critique against his government’s decision to confiscate large swaths of land from the adjacent villages to future Karmiel, Levi Eshkol, then the Prime Minister of Israel, wrote a letter in October 1964, stating:

The fact is that Karmiel, the youngest of our development towns, has already brought about prosperity to the Arab residents in the area. Testimony to this are the many tens of workers from nearby villages who are already employed on the site and no longer need to commute the distances [to Haifa and Acre], and the aqueduct that delivers drinking and agricultural water to the area’s villages, as well as the electric line approaching the region.

Eshkol added:

The “Luddite-like” objection to the development plan reminds me of Jewish waggoneers within town bounds who said that a train line to the town will have to run “over their dead bodies,” as they laid upon the ground with their whips in their hands in order to delay the construction. The train [track] was built – and they adjusted to the new era for their own benefit and wellbeing. This will surely happen in our case. I cannot but wonder how people whose mindset is far from primitive can identify with this [Palestinian] rebelliousness (Eshkol to Martin Buber, 1964).

If the quote with which I opened, about the destruction of Palestinian landscapes, positioned infrastructure as profound interruption – as elimination and replacement – then the latter quote from Levi Eshkol represents infrastructure as advancement. Infrastructural ‘improvement regimes’ have been the epicentres of urban colonisation for centuries, and they continue to perpetuate structures of racial capitalism in cities today (Ranganathan, 2018). Indeed far from mundane, infrastructural projects are better understood as a ‘calculative rationality and a suite of spatial practices aimed at facilitating circulation – including, in its mainstream incarnations, the circulatory imperatives of capital and war’ (Chua, Danyluk, Cowen, & Khalili, 2018, p. 618) . The logistics of establishing an urban colony in the Galilee sit at the heart of the ongoing colonial warfare in Palestine-Israel.

Nevertheless, it is true that only with Karmiel’s establishment did the villages of Beit HaKerem Valley were first provided with running water and household electricity. Of course, this does not undo the gross injustice of their dispossession, but in turning our gaze to the materialities of the Judaisation project – its effects rather than stated intentions – the doings of colonial infrastructure matter. While Israel used modern infrastructures – electricity, sewage, roads – to undo some of the region’s former infrastructures, colonial infrastructures of ‘improvement’ also opened avenues for Indigenous continuity. I show below that Palestinians were taken into account in the very establishment of these colonial infrastructures and that rather than rendering the Palestinian landscape a matter of the past (as Eshkol’s quote would suggest), the project of building a Jewish city in the Galilee reaffirmed the Palestinian identity of the region.

Sovereignty Under Construction

Viewed quite negatively – for different reasons – by both Palestinians and Jewish settlers at the time, the establishment of Karmiel relied heavily on a non-Jewish labour force. Even as the city was already being populated, Jews were predominantly employed outside of Karmiel. It took a good few years before the local industry was developed enough to offer professional opportunities to urban residents. Throughout this period, Palestinians remained a majority presence in the city. In July 1964, the Regional Employment Supervisor in Haifa and the Northern District observed about Karmiel:

The construction industry currently employs about 195 people, of them 25 are Jewish […]. An odd phenomenon in my opinion is that once the workday is over, there remains not even a single Jewish soul in the area. […] in the future – I was told that matters will change when the settlers arrive.

In response, the Director of Employment and Immigration in the Northern District sought clarification about the origin of existing workers. The Supervisor replied:

[…] contracts were granted to Arab subcontractors from the region. A total of 240 Arab workers and 40 Jewish workers […], are employed on site, in addition to 10 Jewish managers. The Arab workers are mainly from the surrounding villages: Rame, Sajour, Bi’na, Dir al Asad, Majd al Krum and Acre. For the Arab workers this is a relief since they no longer have to commute the distances [to work] .

This exchange demonstrates that Palestinians were highly involved in setting up the (Jewish) urban infrastructures. Yet they were mainly involved as labourers, while the managers were for the most part Jewish. We cannot, nor should we, overlook Marx here; Israel induced in the Galilee a structure of exploitation that was built on Palestinian proletarianisation. As Yair Bauml (2007) observed, once Israel had expropriated Palestinians’ lands and driven their economy into the ground, the Palestinian workforce became the ‘last means of production’ to be transferred ‘from the Arab to the Jewish market’ (170). In fact, the destruction of Palestinian agricultural economies ran even deeper; using compressors to drill into the ground and set up an elaborate system of pipes, wires and roads, Israel violently and radically transformed the landscape away from its Indigenous infrastructure. Beyond a horizontal exploitation of the land and its people, Israel set up in the Galilee a vertical settler-colonial infrastructure (following Weizman, 2004).

Notably, the Employment Officer’s concern that Jews are hardly present in the emerging city indicates that beyond employment, the construction site of Karmiel was also one of identity-making and contested territorial control. This is because Palestinians were effectively and undesirebly indispensable; they could not be replaced or entirely removed from the land since they were integral to the making of the Jewish city. Israel’s dependence on Palestinian labour for establishing Karmiel served as a reminder of their primacy and endurance in the landscape, which troubled Israel’s settler sovereignty.

My argument relies on Elizabeth Povinelli’s (2011) criticism of the liberal ‘governance of the prior’, which denotes the universally accepted notion that as a natural rule, ‘what was must remain’ until and unless something new is installed in its place. This natural law predates the settler-colonial state’s conflict with Indigenous people. As Povinelli (2011) explains:

The seizure of persons […], property […] and territory […] were all articulated through the still emergent notion that what held must hold until it is purchased (or gotten by treaty), forced to give way (through conquest or genocide) or characterized as never having actually existed (such as in the concept of terra nullius) (17).

‘Possessing the quality of the prior’ has legal implications for it is a global order of recognition. While expulsion, destruction, and violent seizure remain viable measures in the governance of the prior, they have become less common in liberal regimes. More common is the discursive practice of ‘smoothing’ the prior into a linear timeline that constitutes the past – which is of course still present – as ‘reforming’ or ‘under construction’ (a ‘past-perfect’ in Povinelli’s terms). By rendering the prior a part of the settler ‘future-perfect’ (Kowal, 2015), the state reduces its edge and claim as a prior, while also reaffirming its so-called inclusive or multicultural future (Higgins, 2019).

In Israel, the liberal governance of the prior manifested in one of the state’s earliest decisions to grant Israeli citizenship to Palestinians who remained in the territory at the end of the 1948 war. As Shira Robinson (2013) explains, the naturalisation of approximately 150,000 Palestinians – following the displacement of 750,000 Indigenous inhabitants by Israeli forces during the war – was prompted first, by international pressures to ‘do the right thing’ and second, by a desire to swiftly demarcate the state’s sovereign borders and prevent the return of Palestinian refugees. Naturalisation, Israel anticipated, would undermine claims by Palestinian citizens that they are still (somehow) colonised. Crafted as a liberal settler state (Robinson’s term), Israel used the instrument of naturalisation as a way of undoing Palestinians’ legal status as the prior.

Returning to Karmiel, we might recall that Eshkol situated Palestinians as an ‘under-construction’ past and the settlement as the region’s progressive future. Despite opposite intentions, the inclusion of Palestinians into the so-called inevitable modernisation of the Galilee reinforced the potency of their prior occupation. As we saw, relying on Palestinians to build the Jewish city was unsettling. Moreover, while coercively included into Israel’s colonial regional development, Palestinians never ceded their claims to the land. As the two villagers in my opening account clarified, this was never an agreed upon resolution; they refused to give up their land and the land remains a part of their soul. From an Indigenous perspective, sovereignty need not be articulated or directly asserted for the conflict to remain present and real.

Today, Palestinians are deeply involved in Karmiel’s political, social and economic life and many of them are residents of the city (Blatman-Thomas, 2017). Palestinians own businesses in Karmiel, manage retail shops and offices and offer highly skilled professional services to its Jewish residents (Fig. 5). As a ‘mixed’, rather than exclusively Jewish city, Karmiel did not fully accomplish its intended objectives. The logistics of building a new city in the Galilee forged a range of opportunities for Palestinians to remain collectively connected to the lands they were dispossessed of. Thus, rather than situating Palestinians exlusively within the Jewish time-tale, the infrastructural colonial project left profoundly unresolved questions of sovereignty, ownership, and belonging in the western Galilee.

Works Cited

Bauml, Y. (2007). A Blue and White Shadow: the Israeli Establishment’s Policy and Actions among its Arab Citizens, the formative years: 1958-1968. Haifa: Pardes.

Blatman-Thomas, N. (2017). Commuting for Rights: Circular Mobilities and Regional Identities of Palestinians in a Jewish-Israeli Town. Geoforum, 78, 22-33.

Chua, C., Danyluk, M., Cowen, D., & Khalili, L. (2018). Introduction: Turbulent Circulation: Building a Critical Engagement with Logistics. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 36(4), 617-629.

Higgins, K. W. (2019). Tense and the other: Temporality and urban multiculture in Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 44(1), 168-180.

Kowal, E. (2015). Time, indigeneity and white anti-racism in Australia. 26(1), 94-111.

Leshem, N. (2016). Life After Ruin: The Struggles Over Israel’s Depopulated Arab Spaces (Vol. 48): Cambridge University Press.

Ranganathan, M. (2018). Rule by difference: Empire, liberalism, and the legacies of urban “improvement” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, online first.

Robinson, S. (2013). Citizen Strangers: Palestinians and the Birth of Israel’s Liberal Settler State. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Weizman, E. (2004, 12 January 2004). The Politics of Verticality. Mute.